Key Highlights

Amidst the ongoing loneliness pandemic, the consumer is caught in a loop; they feel the lack of community, and these brands offer a branded substitute. Gen Z’s obsession with identity inevitably leads to the perfect consumerism trap. The widespread exploration of sexual identity, personal style, and personal branding - all these components lead to more purchases. More time is spent on screens to curate an identity, rather than a lived experience that shapes one’s character.

There is a quiet, significant shift happening in the branding industry, a shift solidifying the fatigue we all feel towards consumerism. The goal is no longer to be seen buying a luxury item, but to be unseen within an exclusive experience, to trade the currency of cash for the far more valuable currency of social access. But can you afford the entry fee?

This inconspicuous marketing strategy is adopted by brands that seek to re-establish exclusivity. “Quiet luxury” could have been the very first sign of this revamp. The term emerged after events such as Sofia Richie's elegant wedding, which was estimated to cost around $4 million, and after the beloved show, “White Lotus,” which depicts rich people residing in foreign luxury resorts, sparked a web of conversations on social media platforms. Surprisingly, the rich weren’t ridiculed; they weren’t praised either; they were rendered relatable.

This sliver of empathy was strategically co-opted by the industry as “community-based experience” - the commercial equivalent of a “Third space.” This terminology was coined by Sociologist Ray Oldenburg, who deemed it important to have a third place aside from home and work, where people gather to enjoy the company of others. Brands utilize community events to drive up sales. The carefully maintained 'relatability' of the always-accessible influencer is now giving way to a new model: curated exclusivity.

Notably, direct marketing isn’t extinct, but luxury brands or those no longer wanting to be associated with rapid consumption are pivoting to smaller, more niche, purportedly exclusive events. Brands understand that you can’t replicate experience.

Who is invited?

Typically, it is carefully selected ambassadors of a brand. It may be a well-known influencer, whose recent makeover adheres to the brand's image. However, it is also renowned photographers, journalists, culture critics, and any creative with a substantial background. This curated pool of elites projects an image to the consumer, who is never invited but seeks to create a similar likeness.

Tommy Hilfiger, this past summer, invited a bunch of model influencers to the Caribbean for a brand trip. The brand covers travel and accommodation fees, luxurious activities like boat rides, surfing, and private island dinners, in exchange for shooting content. Everyday consumers are not on the guest list, but can buy the look to attempt to replicate this haute gamme holiday.

Simultaneously, other brands use pop-up events, which have been circulating for quite a while; this version of a community event allows everyone in. According to a 2023 Salesforce report, 80% of consumers say the experience a company provides is as important as its products and services. However, this form of inclusivity permeates the subconscious of consumers, leading them to believe they are one step closer to exclusive events and limited edition items, which often require exclusive links, a password-protected entrance, or affiliation. Brands are selling dreams that were never meant for the consumers to begin with.

The Loss of Third Places

During the COVID-19 pandemic, a lot of businesses had to shut down or downsize, and with the lockdown rules keeping everyone at home, it caused a rupture in the symbiotic relationship between regulars - that is, frequent customers - and the establishments. The main industries affected were beverage-serving and arts, entertainment, and recreation, with the beverage-serving industry harbouring a 92% fall in turnover and a 64% for the latter, stated in a 2023 report by The Office for National Statistics. The entertainment industry still proves to fall below pre-pandemic levels, as only 4% of adults attended cinemas around the easing of lockdown rules in 2021.

This amalgamation of issues delivered a colossal hit to the social sphere, and consequently, to third spaces. Social distancing resulted in longer queues, which are prevalent today. Businesses were forced to pivot and find alternatives to maintain their operations. Thus began the era of pop-up events, limited sales, and the rise of the new hip bar or cafe with restricted seating - all catering to an even more eager crowd yearning for their much-awaited promised freebies.

This replicated format of an illusioned third space by brands exacerbates the ongoing disappearance of tangible third places that have been a pillar in communities. The pandemic primarily impacted local businesses compared to bigger business franchises. A Greater London Authority Report accounts for 1,010,000 small businesses in London, with only 13% of the country’s population, it generates more than 23% of the national economic output. The Arts and Entertainment sector during COVID was predicted to have one of the highest impacts, with 21% of SMEs (small businesses) affected.

As these local venues struggled or vanished, the vacuum wasn't left empty; it was filled by a different model entirely. London’s entertainment spots are transforming into homogeneous high streets, totally unrecognisable to long-time Londoners. The U.K. staples like Cafe Nèro, Costa, and WHSmith are being replaced by American franchise companies, Blank Street Coffee - which already has 10 spots in the city, Black Sheep Coffee, Taco Bell, and Popeyes, just to name a few. In the craze of matcha, some cafe franchises have adapted to the demand by basing their sales mainly on matcha products. You can have a blueberry oat matcha latte for £5, but this commercialized trend drives independent cafes into insolvency. A traditional Japanese cafe offering ceremonial matcha teas has to compete with thousands of funded advertisements from bigger franchises.

This doesn’t just erode local businesses; it attacks the very infrastructure of bumping into acquaintances, fostering new relationships with regulars - the unplanned conversations that spark to creative projects, romantic encounters, or platonic bonds. It dismantles the simple, profound joy of conversing with another human.

Where are we going wrong?

Loneliness may be responsible for 871,000 deaths each year. Many case studies show that the pandemic has increased the rate of isolation. More young people are switching from their physical communities to a virtual one. British psychologist Robin Dunbar believes we can only retain 150 people in our lives, and that is divided into six sectors; the closest of friends are approximately five people, then 15 good friends, 50 friends, 150 meaningful contacts, 500 acquaintances, followed by 1500 people you can recognise. Whether this rings true or not, Dunbar's research shows that those aged 18 - 24 have much larger online social networks than those aged 55 and above. Evidently, the quality of the friendship for both age groups depends on how much time is devoted to them.

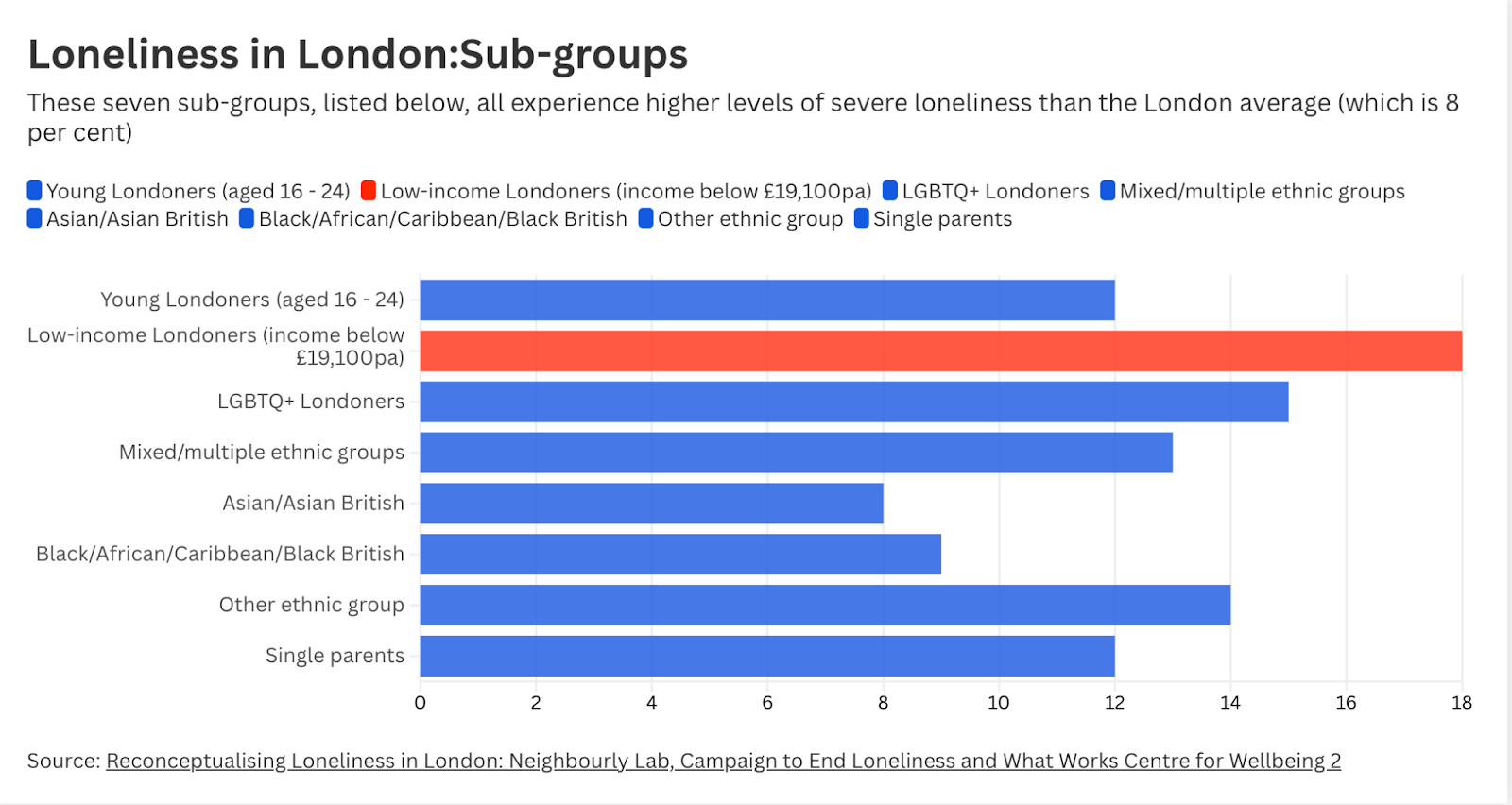

Data Graph shows Loneliness in London.

Amidst the ongoing loneliness pandemic, the consumer is caught in a loop; they feel the lack of community, and these brands offer a branded substitute. Gen Z’s obsession with identity inevitably leads to the perfect consumerism trap. The widespread exploration of sexual identity, personal style, and personal branding - all these components lead to more purchases. More time is spent on screens to curate an identity, rather than a lived experience that shapes one’s character. According to Media regulator Ofcom, 18-24-year-olds are spending an average of six hours a day on social media, with women spending an hour and eight minutes more than men.

The online world is becoming a third space of its own. Brands that are pivoting to a more niche marketing strategy are inhabiting these virtual spaces with their own online hubs, personalized quizzes (shopping by zodiac signs), online newsletters, blogs (talks of pop-ups and recent gatherings), and personalized recommendations, exacerbating an already prominent issue with overconsumption and the link to social isolation.

What happens next?

Although not everyone is invited to the party, creating and maintaining authentic communities is the biggest talking point on social media amongst the younger generation. Nostalgic sports like parkour and free DJ events are encouraging people to step out and maintain the pillars of socialisation. There’s also an uptick in being off-grid by having no to little social media presence. Some clubs are also initiating a ban on phones from their venues to encourage people to remain in the present moment. These prime examples are a pushback against the online bubbles a lot of Gen Zs feel stuck in.

The youth are reevaluating what community means outside of commerce. Perhaps enjoying breakfast at a local cafe amongst regulars is often better than being with strangers in a fabricated space.