🎧 Listen to the Article

This audio is AI-generated for accessibility.

Key Highlights

England’s first tuition fee rise in nearly a decade is set to reshape the landscape of higher education, pushing the annual cap above £9,250 and deepening questions about affordability, value, and access. With student debt already averaging £45,000 at graduation and living costs climbing, the 2026 increase threatens to widen inequalities and intensify pressure on young people navigating an unstable economy. Universities argue the rise is essential after years of funding erosion, but students, families, and social-mobility advocates warn it may place higher education further out of reach. As the nation stands at a crossroads, the debate over who should bear the cost of a degree and what that cost represents has never been more urgent.

For the first time in almost a decade, the cost of going to university in England is about to rise. From September 2026, the long-frozen tuition fee cap, held at £9,250 since 2017, will rise in line with inflation, marking a significant recalibration of how the nation values knowledge and funds access to it. The move exposes a central tension in British life: the uneasy balance between education as a public good and as a private investment. For universities, it promises a financial lifeline; for students, it signals a new era of debt and doubt.

Students across the country are taking on unprecedented levels of debt in order to access higher education. The House of Commons estimates that the average student now graduates owing around £53,000, a sum many will never fully repay. Entering adulthood burdened by effectively unpayable debt, while simultaneously navigating a cost-of-living crisis and a housing market increasingly out of reach, has left many students and recent graduates feeling trapped.

For years, young people have been told that a university degree is the essential pathway to a stable career and, eventually, home ownership. Yet for a growing number, these milestones feel ever more distant. Starmer’s proposed rise in tuition fees threatens to widen this gap further, intensifying debate over the true value of a degree and the long-term consequences for those graduating into an already precarious economy.

The Rising Tension Between Costs and Quality

University tuition fees were first introduced under Tony Blair’s Labour government in 1998 at £1,000 a year, and have risen steadily to today’s £9,250 cap. Several forces have driven this escalation. Foremost is the mounting cost of running modern universities: institutions face rising expenditure on staff salaries, campus facilities, digital infrastructure, and essential maintenance. As public funding has failed to keep pace with these pressures, universities have increasingly relied on tuition income to bridge the gap. In practice, this has meant passing a growing share of operational costs directly onto students through higher fees.

The decision, long anticipated by policy analysts, reflects deep structural pressures within the university sector. Over the past decade, inflation has quietly eroded the real value of tuition income, leaving many institutions struggling to sustain teaching quality, research capacity, and student services. According to the Department for Education’s 2024/25 Impact Assessment, the £9,250 tuition-fee cap, unchanged since 2017, has lost significant value due to inflation. In 2012/13 price terms, the fee is now worth £5,860, meaning its real-terms value has fallen by around 37% since the cap was introduced. The Institute for Fiscal Studies has also highlighted the erosion of funding, noting that per-student teaching resources are now back to roughly 2011 levels in real terms, despite rising costs across the sector. Together, this data shows that the headline fee universities receive today purchases far less than it did a decade ago, leaving institutions under growing financial pressure even before the planned 2026 fee rise.

Yet for students, survival has its own price. The proposed inflation-linked increase could push annual tuition above £10,000, adding thousands to the typical graduate’s debt. Against the backdrop of rising rents, energy bills, and food costs, the fee hike risks tipping a generation already navigating economic precarity into greater financial insecurity.

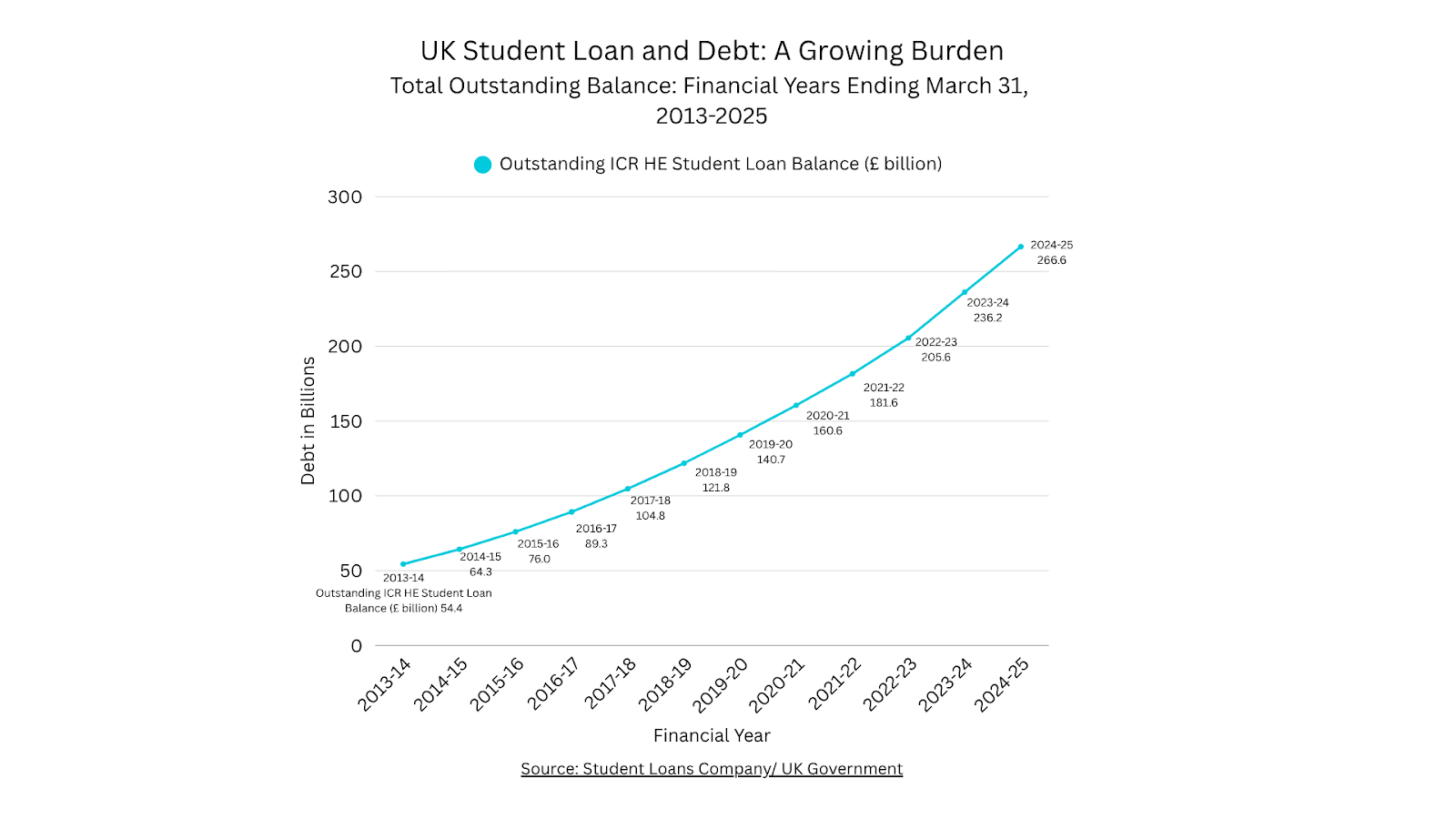

Graph created by Elise Gregory

Outstanding student loan debt in England has climbed to £266.6 billion, almost five times the level in 2013–14, according to new Student Loans Company figures. Debt has risen steadily from £54.4 billion a decade ago, accelerating during the UK’s cost-of-living crisis as inflation pushed living costs far beyond maintenance loan levels, forcing many students to borrow more for essentials.

New graduates entering repayment now owe an average of £53,010, highlighting the pressure on young people whose wages have not kept pace with rising prices. The sharp £30.4 billion jump between 2023–24 and 2024–25, driven by higher lending and £15.2 billion in interest, marks the biggest annual increase yet. With the arrival of Plan 5 loans extending repayment for future cohorts, the steep upward trend in the graph mirrors the broader squeeze of the cost-of-living crisis.

Access, Equity, and the “Price of Opportunity”

At its core, the debate is about accessibility: tuition fees have long been framed as either a gateway or a barrier to social mobility, and the proposed increase risks deepening existing divides. Students from regions with historically low university participation may be disproportionately deterred by rising costs, while those from wealthier households are better positioned to manage higher fees, widening socioeconomic gaps. Subject choices may also shift, as degrees in lower-earning fields such as the arts, humanities, and social care become less financially justifiable under increased debt expectations, threatening the diversity of academic disciplines. Beyond the numbers, there is a growing psychological toll; in a climate of economic instability, the prospect of graduating tens of thousands of pounds in debt adds emotional weight to academic pressures, making the idea of beginning adult life “in the red” increasingly unpalatable for many young people.

Chloe Field, Vice President for Higher Education at the National Union of Students, warns that the proposed 2026 tuition fee rise risks worsening existing inequalities. “Students from lower-income households are already making impossible choices between working part-time, supporting family, or studying full-time,” she explains. Field emphasises that fee increases do more than add financial pressure, they shape who feels able to access higher education at all. Supporting this view, a senior researcher at the Sutton Trust highlights that rising costs disproportionately affect students from regions with historically low university participation, potentially reversing years of progress in social mobility. The Social Mobility Commission echoes these concerns, noting that without targeted measures, the fee hike could entrench socio-economic divides and leave the most disadvantaged young people further behind.

Is It Still Worth It?

The question hanging over the debate is deceptively simple: is a degree still worth it? While graduates continue to earn, on average, more than non-graduates, the gap is narrowing. Under the government’s new loan system, most students will repay for 40 years, a lifetime of deductions that, for many, will never fully clear the balance.

As tuition fees rise, so too does scrutiny of what students receive in return. Value for money, once a fringe concern, has become central to the national conversation. Students expect stable contact hours, robust academic support, mental-health services, and pathways to employment.

Graduate labour-market outcomes complicate the value debate as they remain positive on average, LEO data show that working‑age graduates in England still earn significantly more than non‑graduates, with recent figures putting the gap at around £10,500 per year. However, returns vary considerably by subject, institution, and socio‑economic background: IFS analysis of LEO data shows that although all groups benefit from a degree, the size of the earnings premium and its trajectory differ markedly, raising complex questions about the uniform value of higher education.

Yet satisfaction surveys in recent years reveal mixed experiences. While many institutions have invested in digital tools, blended learning, and facilities upgrades, students report ongoing challenges: overstretched support departments, housing shortages, crowded seminar groups, and inconsistent feedback quality. The question lingers: If the price of a degree increases, will the experience improve, or merely cost more?

Emma Parsons, 26, graduated three years ago with a degree in social work, a field she loves but one that does not pay as well as law or finance. She entered adulthood carrying around £45,000 in tuition debt, a burden that continues to shape her daily life. “Even with a full-time job, most of my salary goes to rent, bills, and living costs,” she explains. The weight of repayment has delayed major milestones such as saving for a home and has forced her to turn down low-paid or unpaid opportunities that might have advanced her career. Emma worries that rising tuition fees will deter future students from essential but lower-earning professions, leaving only high-paying fields accessible and undermining the diversity of the workforce. “Debt isn’t just a number,” she says. “It affects life decisions, mental health, and the kinds of careers people feel they can pursue.”

The Future of Opportunity

Alternatives are gaining ground. Degree apprenticeships, online learning, and vocational programmes are drawing students who prioritise affordability and employability. Still, for many, the university remains both aspiration and necessity, a cultural marker of success as much as an educational experience. The 2026 fee rise may not end that aspiration, but it will undoubtedly redefine who can pursue it.

As England approaches this inflection point, one truth becomes clear: the conversation about tuition fees is not just about money. It is about what kind of society Britain wants to be, one that views education as a collective investment, or one that continues to commodify the pursuit of knowledge itself.

A Turning Point for Higher Education

Whether the 2026 tuition fee rise stabilises the sector or destabilises student confidence remains to be seen, but what is clear is that the decision will shape England’s higher-education landscape for years to come. Potential consequences range from shifts in student demand, driving more young people toward apprenticeships, accelerated degrees, part-time study, or non-university pathways, to rising financial pressure on families trying to save for future education. The change is also likely to intensify calls for structural reform, reigniting debates over graduate taxes, means-tested fees, or fully publicly funded models, while widening the gap between financially secure universities and those already struggling to stay afloat. Ultimately, the tuition fee rise is more than a simple pricing adjustment; it represents a fundamental recalibration of what opportunity costs in England today.

A Nation at a Crossroads

As England prepares for the first tuition fee rise in almost a decade, the stakes extend far beyond university balance sheets. The debate touches on fundamental questions about fairness, economic mobility, and the purpose of higher education itself. The decision to raise fees may help keep universities afloat, but at what cost to the next generation? And if the price of a degree continues to climb, will the promise it once held remain within reach?