🎧 Listen to the Article

This audio is AI-generated for accessibility.

Key Highlights

As the government moves closer to lowering the voting age to 16, Britain is being forced to confront who its democracy is designed to include. With young people already politically active and deeply affected by long-term policy decisions, the question is no longer theoretical, but whether the system is ready to meet them as voters.

Across Britain, young people are navigating a political landscape that they have little formal power to shape. They face spiralling housing costs, an increasingly unstable climate, rising student debt, and public services weakened by years of austerity. Many of them entered adolescence during a pandemic that disrupted education and exacerbated inequality. Yet, despite being directly affected by nearly every major policy debate, millions of Britain’s young people are excluded from the ballot box.

The question of whether the UK should lower the voting age to 16 has resurfaced many times before, often framed as a theoretical or symbolic reform. In July 2025, however, the debate shifted decisively. The government confirmed that extending the vote to 16-year-olds had become an active policy plan, moving the issue from the margins of political discussion to the centre of democratic reform. In that context, the focus is no longer simply whether young people should vote, but whether the political system is prepared to support them as full democratic participants.

During parliamentary discussions, ministers argued the change would strengthen democratic participation by aligning voting rights with responsibilities such as work and tax contributions, and pledged to support improved registration and engagement among young voters. Prime Minister Keir Starmer said young people “who pay in” should have a say in how public money is spent. However, Conservative MPs like Paul Holmes criticised the move as inconsistent, noting that 16-year-olds still cannot stand for Parliament or engage in many adult activities, while political figures such as Nigel Farage have warned the reform could shift the electoral balance.

The debate over lowering the voting age has endured for so long because it exposes a persistent discomfort about who democracy is really for. Since the franchise was extended to 18-year-olds in 1969, governments of all stripes have treated the voting age as politically sensitive territory, wary of reshaping the electorate or appearing to gamble with democratic norms. Youth participation has repeatedly been framed as a question of maturity rather than representation, even as young people have taken on adult responsibilities earlier and in increasingly precarious conditions. Each wave of youth activism has brought the issue back into view, only for it to be deferred once more. What sets the current moment apart is not a sudden change in principle, but the sense that delay itself is becoming harder to defend.

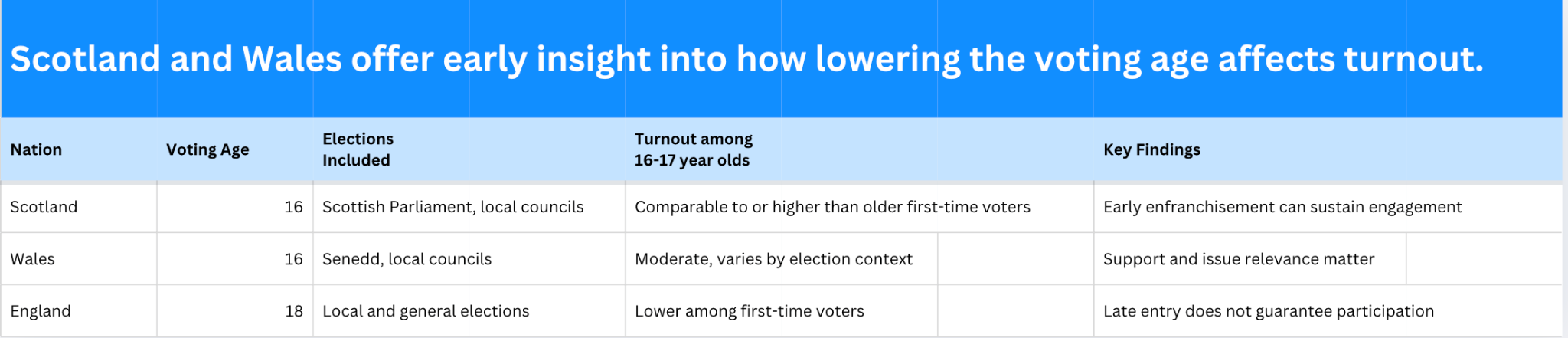

Scotland and Wales have already lowered the voting age for local and devolved elections, creating a natural experiment within the UK itself. Early data from these nations suggests that turnout among newly enfranchised 16- and 17-year-olds can be strong, particularly when supported by civic education or when elections focus on issues that feel immediately relevant to young lives. Research by the School of Social and Political Science at the University of Edinburgh has found that 16 and 17-year-olds have voted in higher proportions than older first-time voters and have maintained higher turnout into their early twenties.

Callum Fraser, 21, a politics student at the University of Edinburgh, voted for the first time at 16 in Scotland and says he felt prepared because politics was already part of everyday life. “The independence referendum and later elections were everywhere, at school, online, at home,” he says, adding that teachers took time to explain how the process of voting worked and why it mattered. Voting early, he argues, changed how he engaged with politics: “Once you’ve voted once, you start paying more attention. You feel more accountable for your views.” At the same time, Fraser is clear that readiness is not universal. “Not everyone is at the same place at 16,” he says, pointing to uneven access to political education and confidence. For him, the lesson is that “the focus shouldn’t just be on age, but on preparation,” and that treating young people as participants rather than a risk can make democratic engagement feel like a responsibility rather than an obligation.

Concerns about political maturity are often central to opposition to lowering the voting age. Yet recent research complicates that assumption. A 2025 peer-reviewed study examining political reasoning among adolescents found that their ability to understand political choices, weigh competing arguments and make decisions consistent with their values was broadly comparable to that of adults. The findings suggest that age alone is a poor proxy for democratic competence, and that factors such as education, access to information and political context play a far greater role in shaping how people vote, regardless of whether they are 16 or 60.

The argument often hinges on readiness, but the threshold for political competence is already uneven. Many adults vote with limited policy knowledge, minimal engagement, or misinformation. Meanwhile, many 16-year-olds are in structured settings, schools, colleges, youth programmes, where political education can, at least in theory, be supported more reliably than among older demographics. The question becomes not whether teenagers are uniquely unprepared, but whether they are being held to a standard that adults themselves do not meet.

Some of the strongest arguments for lowering the voting age come from considering the responsibilities young people are already expected to shoulder. At 16, many are working part-time, paying taxes, and contributing economically while holding no say in how public revenue is spent. Others are apprentices, young carers, or care leavers managing adult responsibilities long before their eighteenth birthday. In many parts of the country, citizenship education is patchy, under-resourced, or absent altogether, a structural issue that punishes young people but could be addressed if the political system viewed them as full participants rather than future ones.

Sarah Steward, Programme Coordinator at Young Citizens UK, emphasises that young people are already engaging with politics in meaningful ways. “Through schools, youth councils, campaigns, and social media, many 16- and 17-year-olds are debating issues and following how government decisions affect their lives,” she says. Granting them the vote, she argues, would recognise this participation and help it grow. Steward stresses the importance of structured support: “Readiness isn’t just about age; it’s about access to information and opportunities to develop civic skills. If the voting age is lowered, we need a coordinated effort to ensure every young person has the tools to make an informed choice.” Without adequate civic education and mentoring, she warns, young voters risk disengagement, but with proper guidance, they can participate confidently and responsibly.

Opponents raise genuine concerns. Lowering the voting age requires investment in political education that successive governments have repeatedly sidelined. Digital misinformation poses risks for all voters, but particularly for those whose media literacy varies widely depending on region, school funding, and class. There is also the question of turnout: if 16–17-year-olds vote in low numbers, critics will claim it proves the experiment a failure.

A 2025 poll conducted by the University of Glasgow found that many 16- and 17-year-olds do not feel confident navigating politics or casting a vote. While they are keen to have a say in decisions that affect their lives, the research suggests that enthusiasm alone is not enough. Respondents emphasised the need for stronger citizenship and democracy education, warning that lowering the voting age without adequate support could leave young voters underprepared. The findings highlight a wider structural challenge: ensuring that legal enfranchisement is matched by accessible, consistent, and practical political education that equips young people to participate fully in the democratic process.

But these challenges do not negate a central democratic principle: those who are affected by political decisions should have a voice in making them. When a generation is facing the long-term consequences of climate policy, economic reforms, and public spending decisions, excluding them becomes harder to justify. Lowering the voting age would not solve Britain’s democratic malaise on its own, but it would acknowledge the political reality that young people are already participating, just not through the mechanisms the state recognises.

Emma Thompson, 19, a Politics and International Affairs student at King’s College London, believes lowering the voting age to 16 is long overdue. “By 16, you’re already making important decisions about your future, your education, work, even finances. It seems strange to have responsibilities but no formal say in the system that governs you,” she says. She adds that social media and news apps give teenagers access to real-time political information, allowing them to debate issues and make informed choices. While schools still need to teach political literacy beyond exams, Thompson notes that many young people are already engaged, following news, volunteering, and campaigning on issues that matter to them. Formal voting rights, she argues, would recognise the participation that is already happening.

Lowering the voting age to 16 is no longer an abstract question about youth engagement, but a test of democratic legitimacy. As the government moves closer to reform, the issue becomes less about whether young people meet an idealised standard of political readiness and more about whether the state is willing to invest in the conditions that make participation meaningful. Education, access to reliable information, and trust in young citizens will determine whether reform strengthens democracy or exposes its weaknesses.

Britain now faces a clear choice. A generation that is politically active, digitally fluent, and deeply affected by long-term policy decisions is already shaping public debate from the outside. If the franchise expands, the responsibility will sit not only with new voters, but with institutions to meet them halfway. Whether the voting age is lowered or delayed, the pressure to align democratic power with social reality is no longer something the political system can defer, particularly now that reform is no longer hypothetical.