Key Highlights

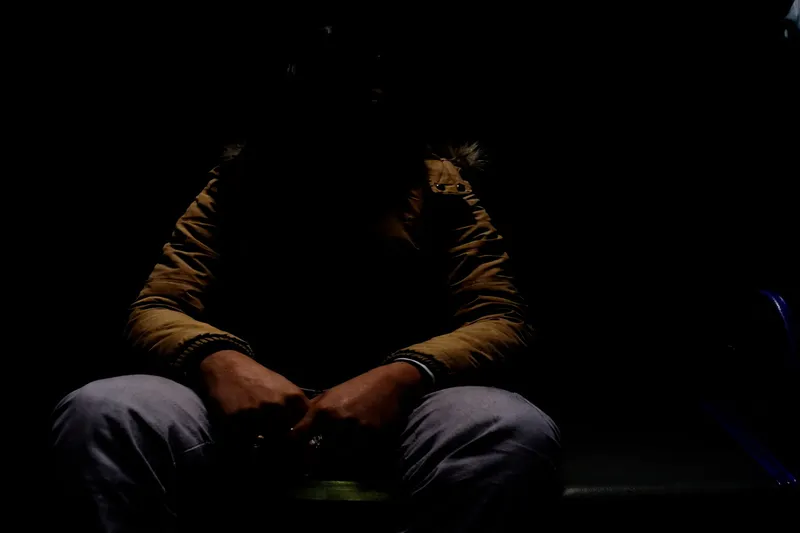

Undercover reporting (UR) breaks the rules, barriers and principles of conventional journalism to protect the public interest. When traditional journalism is locked out, undercover reporting steps in. From hidden hunger in North Korea to secret political influence campaigns, this article examines how journalists break rules to reveal the truth by going undercover, and why deception remains one of journalism’s most controversial yet most necessary tools, often at severe personal, legal, and psychological risk.

What is the price of a hidden truth?

In 2010, a story resurfaced of a young woman in North Korea who told an undercover reporter she was eating "nothing" shortly before she starved to death.

This reality would be invisible if not for Undercover Reporting (UR), which is journalism’s most paradoxical and ethically fraught tool. By choosing deception over transparency, UR enters the spaces where traditional reporting hits a dead end: locked gates, censored nations, and systems designed to hide themselves.

UR is one of journalism’s most paradoxical tools.

It is a high-risk but high-impact form of investigation in which journalists conceal their identity or purpose, often entering organisations or environments as insiders to reveal wrongdoing, hidden conditions, or abuses that cannot be uncovered through traditional reporting methods.

UR relies on deliberate deception, utilising hidden cameras, false names, and covert infiltration, to reveal information that cannot be obtained openly. It deliberately violates core journalistic principles such as transparency and informed consent, which is precisely why it remains one of the profession’s most controversial practices.

Newsrooms treat it as a measure of last resort, used only when the public interest clearly outweighs the ethical breach.

Yet UR endures because some stories cannot be uncovered through traditional journalism, those unfolding behind locked gates, within censored nations, sealed institutions, or systems designed to evade scrutiny.

This article begins where journalism’s ideals collide with real-world obstructions, and where truth survives only because someone willingly decides to go in disguised, unnoticed, and uninvited, with an extreme level of risk, if exposed.

North Korea: A Human Moment the World Would Have Never Seen without UR

In December 2025, the Facebook page Wild Heart shared a short account from undercover reporting inside North Korea.

When he asked what she ate herself, she reportedly whispered one word: “Nothing.”

Four months later, the young woman was found dead in a cornfield, likely trying to survive on raw kernels. Local authorities left her body where it was found, a truth that would likely never have surfaced in a closed nation where food scarcity is officially denied.

The Facebook post reminded readers that some realities only reach the world because some unconventional reporters are willing to document them covertly, risking their lives.

BBC Panorama: Hidden Cameras Inside a Failing British Prison

A similar pattern appears far from North Korea, inside the UK’s own prison system.

In 2017, BBC Panorama placed an undercover reporter, Joe Fenton, inside HMP Northumberland as a prison custody officer, where he secretly filmed widespread drug use, loss of control on the wings, and exhausted staff struggling to cope with prisoners high on the synthetic drug ‘spice’.

The investigation forced a national conversation about the state of British prisons and showed how much remains hidden even in open democracies.

Al Jazeera’s Gun-Lobby Infiltration: Influence Networks Revealed

Al Jazeera reporter Rodger Muller goes undercover in a three-year investigation of the US’s powerful gun lobby’s strategies to promote firearms ownership.

He started his mission in 2015. As an undercover, he assumed the role of a gun advocate, pretending to campaign for a repeal of Australia’s rigid gun control laws, and pretended that he wanted more firearms in the hands of Australian citizens.

The investigation sought to document how gun-lobby groups operated across borders to influence public policy away from public scrutiny.

The investigation exposed how American gun groups quietly advised Australian political actors on weakening national firearm laws, which is a strategy designed to operate out of public sight.

Without going undercover, the coordinated influence campaign would have remained invisible to voters and policymakers.

Why Undercover Journalism Still Matters in 2025-2026

Across the world, press freedom is steadily shrinking. Governments are tightening access to information, corporations are erecting new barriers to scrutiny, and the spread of misinformation is steadily eroding public trust in official narratives.

Many of the most consequential events shaping societies today, from human trafficking networks and extremist recruitment to medical scams and industrial abuse, unfold in environments deliberately closed to outside observation.

In such settings, traditional reporting often reaches a dead end. Authorities may deny journalists entry, powerful institutions restrict what can be seen or recorded, and victims frequently fear retaliation if they speak openly.

At the same time, official versions of events often bear little resemblance to lived realities on the ground, leaving gaps that open reporting cannot fill.

It is within these gaps that undercover journalism becomes indispensable.

By entering spaces designed to remain unseen, undercover reporting enables journalists to expose truths that would otherwise remain hidden.

When used responsibly and as a last resort, it has repeatedly led to public scrutiny, official investigations, and meaningful accountability, reaffirming its relevance even in an era of heightened ethical debate.

The Ethics of Going Undercover

This practice contradicts journalism’s highest values, which is why ethical frameworks become essential before any newsroom approves such work.

Training modules, such as Checkology’s lesson on undercover reporting, explain how editors evaluate these decisions: they first consider whether the story is of genuine public interest and whether the information can be obtained in any other way. They assess if all open-reporting avenues have already been exhausted, and whether the level of deception required is proportionate to the harm being exposed. They must also weigh the risks- both to the reporter and to the people being documented, to ensure that no one is placed in unnecessary danger.

Undercover work, therefore, is never meant to be routine.

It is the last resort for the media world.

It belongs to that narrow space where deception becomes the only morally defensible option left to expose systemic wrongdoing or reveal truths that are deliberately kept out of public view.

What the World Would Never See Without Undercover Methods

Closed systems, whether political, economic, or cultural, rarely allow space for traditional open reporting. They are designed to control access, filter narratives, and prevent scrutiny.

In such environments, some of the most urgent realities remain invisible: state-denied hunger in countries like North Korea, institutional abuse inside prisons and care homes, trafficking routes run by criminal networks, covert influence operations such as those exposed in the gun-lobby investigation, or exploitative workplaces shielded from external oversight.

In India, undercover reporting has also played a critical role in bringing hidden power structures into public view.

Investigative platforms such as Cobrapost and Tehelka pioneered covert reporting methods to expose corruption and influence networks that conventional journalism could not access.

Through undercover investigations such as ‘Operation 136, Operation West End, Operation Duryodhana, and Operation Falcon Claw, these platforms exposed corruption and influence networks that led to national debates, regulatory scrutiny, and high-profile resignations, demonstrating how covert reporting in India has shaped public accountability when open journalism could not.

A Pioneer of Undercover Reporting: Nellie Bly

Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman, better known by her pen name Nellie Bly, occupies a central place in the history of undercover reporting.

She entered journalism at a time when women were largely excluded from investigative work and demonstrated how immersion could be used to expose institutional abuse.

In 1887, Bly feigned mental illness and was admitted to the Women’s Lunatic Asylum in New York.

Over ten days inside the institution, she documented neglect, mistreatment, and inhumane living conditions faced by patients who had no means to speak for themselves.

Her reporting, later published as ‘Ten Days in a Mad-House’, prompted public outrage, a grand jury investigation, and increased state funding for mental health care.

Bly’s work did not rely on hidden cameras or modern surveillance tools. It relied on proximity, observation, and personal risk.

More than a century later, her investigation remains a reference point for immersive reporting, not as spectacle, but as a demonstration of how going undercover can serve public interest when transparency is otherwise impossible.

This is where undercover reporting becomes indispensable: as a way to witness reality from the inside when access is otherwise denied.

Another telling example comes from a ProPublica podcast, which documents the experience of an American journalist who entered North Korea undercover by posing as a school teacher.

The assignment was not aimed at exposing any specific scam or criminal operation.

Instead, its value lay in living and working inside one of the world’s most closed societies. Through everyday observation, the journalist was able to document daily life, restrictions, surveillance, and reveal the atmosphere of control and surveillance that no official tour or open interview could reveal.

The reporting underscored a crucial point: sometimes, undercover journalism is not about uncovering a single explosive revelation, but about making visible an entire reality that is otherwise sealed off from the world.

Together, these cases show why undercover methods continue to matter.

Whether revealing abuse, influence, exploitation, or simply the texture of life inside closed systems, undercover reporting often documents truths that would never surface through traditional journalism alone.

Psychological Cost: The Emotional Strain Behind the Cover

Undercover reporting does not end when an assignment is completed or published. Beyond physical risk and ethical dilemmas, it often leaves a lasting psychological imprint on journalists who are required to live dual lives for extended periods.

Maintaining a false identity, suppressing personal beliefs, and sustaining deception across professional and private spaces can blur emotional boundaries. The strain is compounded by isolation, as undercover reporters are often unable to confide in friends or family while the operation is ongoing.

Rodger Muller’s experience during his three-year undercover assignment for Al Jazeera offers a clear illustration of this psychological toll.

While posing as the founder of ‘Gun Rights Australia’- a fictitious gun-rights organisation, and building relationships with powerful gun-lobby figures, Muller described living with constant anxiety.

In an interview with Australia’s ABC News, he said his early meetings with the NRA were marked by an ongoing fear of being exposed.

“There is always a heightened level of anxiety, and every single meeting was different,” he said.

He explained that even in going back to the same offices, there was no certainty about whether the NRA had changed their security protocol.

“At larger meetings”, he added, “you’d feel like you had an anaconda crushing your chest… but basically, you’d just get through it. You’d internalise it and get on with the job.”

The undercover role also extended into his personal life.

To maintain his cover, Muller said he often had to deflect questions from friends and family about his sudden interest in firearms, publicly advocating views he did not personally hold.

He recalled brushing off doubts by saying, “It’s a scary world out there. I’ve realised that guns can keep us all safe — so I’m campaigning for more guns here”.

The deception, he explained, was not always easy to contain.

Over time, he found it difficult to constantly remind himself that the identity he was projecting was not real. “You start to believe what you’re saying, eventually,” Muller said, adding that the role began to feel normal because it became embedded in his daily routine.

The psychological discomfort did not end when the mission was over.

After returning to normal life and reconnecting with friends and his dog food business back in Australia, Muller acknowledged that the mission lingered in his mind.

He eventually sought help from a psychologist to separate his true self from the fabricated identity he had inhabited for years. “It took two or three sessions to convince her that I was telling her the truth. Eventually, she believed me,” he said.

Experiences like Muller’s highlight a lesser-seen consequence of undercover reporting: the difficulty of stepping out of an assumed identity.

Long after the story is told, the psychological weight of deception often remains, carried quietly by the journalists who chose to go inside so the rest of the world could see.

How Undercover Evidence Leads to Action

Over decades, undercover reporting has triggered investigations, policy reforms, public debates, and a range of official responses.

BBC Panorama’s prison investigation revived national scrutiny of how British facilities are managed, while Al Jazeera’s infiltration of the US-Australia gun lobby reshaped public understanding of the political strategies operating behind closed doors.

Long before these modern cases, Nellie Bly’s landmark investigation into the Blackwell’s Island asylum transformed mental-health oversight in the United States and set a lasting standard for such immersive reporting.

Countless other revelations, from abusive food-processing plants to trafficking networks and corporate misconduct, have surfaced only because journalists went in covertly when no other method would work.

Undercover reporting often succeeds where transparent traditional journalism fails because the evidence it produces is visual, direct, and difficult to dismiss.

The Future: Undercover Work in an Era of AI and Misinformation

The future of undercover journalism is uncertain.

New technologies are making disguise and anonymity far more difficult than before.

AI-driven surveillance, biometric tracking, digital trails, and advanced border screening can expose a false identity within seconds. Even deepfakes complicate the landscape, raising fresh questions about authenticity and trust.

Yet these same technologies are empowering governments and powerful institutions to hide more than ever. As access shrinks and information control tightens, the need for undercover reporting only increases.

That is the paradox of our time: going undercover is becoming harder, riskier, and more constrained, but also more essential if journalists are to uncover what the world is not meant to see.

Conclusion: When Truth Demands Breaking the Rules

Undercover reporting begins where traditional methods fail.

It is journalism’s most ethically uncomfortable form, but also its most revealing.

The moment Kim Dong-Cheul encountered a starving young woman in North Korea, when a BBC guard filmed a prison collapsing under its own weight, or when Al Jazeera exposed political strategies hidden behind closed doors, each of these moments was born of journalists breaking rules in the service of public interest.

Such reporting has never been without cost.

Going undercover means living with deception, exposure, legal uncertainty, and psychological strain- risks that have only intensified in an era of surveillance technologies, digital footprints, and shrinking press freedom.

Yet despite these dangers, journalists continue to step inside closed systems because certain truths simply do not surface any other way.

The world is often not allowed to see what happens in the shadows. Undercover journalists choose to step into those shadows, accepting the risks that come with it, so that the rest of us don’t have to live in darkness.