Key Highlights

Italian media coverage of violence against women often turns a structural phenomenon into episodic spectacle, creating visibility without understanding. ISTAT data show that violence is widespread and rooted in everyday relationships, while gender stereotypes and tolerance of control are reinforced over time by media narratives. Breaking this cycle requires journalism that prioritises context, accountability and explanation over emotional impact.

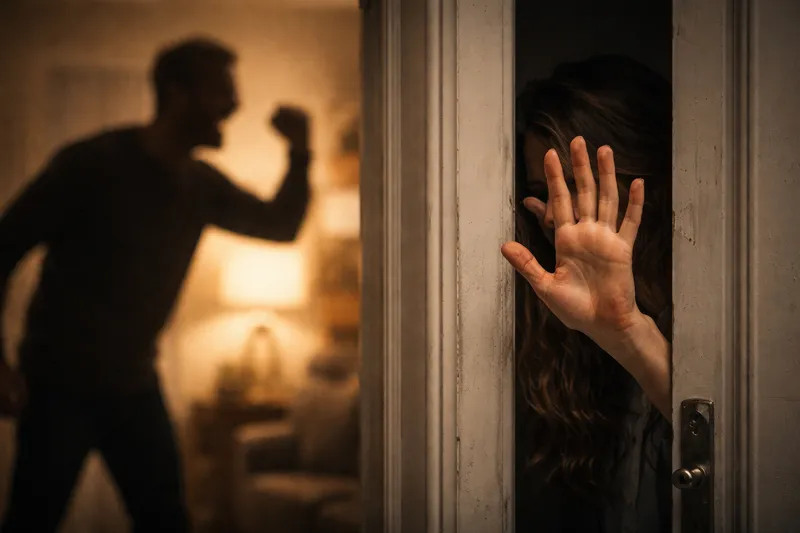

Violence against women is not only a legal or political issue. It is shaped every day by the way Italian media talk about it, sometimes with urgency, sometimes with spectacle, and often with silence.

A recent conference at Sapienza University of Rome, WomenUp. Strategic Alliances and the Media’s Role in Women’s Empowerment and in Combating Gender-Based Violence, offered a rare moment to step back and examine this cycle.

The discussion brought together four voices with different vantage points: police official Barbara Strappato, RAI director Simona Sala, sociologist Massimiliano Padula and actor Daniele Monterosi. Their message was clear: the problem is not only the violence itself, but the cultural lens through which it becomes visible, or invisible, to the public.

When reporting becomes background noise

In Italy, news about violence against women appears almost daily across mainstream television news broadcasts and in newspapers and digital outlets. This stream creates a paradox: instead of raising awareness, it produces a form of emotional numbing that distances audiences.

Since the news broadcast remains the primary source of information for millions of households, these narrative choices carry enormous influence.

The overload of cases, usually presented as isolated tragedies, feeds into what scholars describe as emotionalised infotainment, a mode in which narrative impact takes precedence over explanation. As Rizzuto noted in 2018, Italian media increasingly rely on dramatization and suggestive rather than informative content. In such an environment, violence becomes something to scroll past rather than understand.

The panel warned that this “scroll and forget” rhythm leaves little space for understanding causes or patterns. Without context, the public sees isolated tragedies rather than a structural problem. Official statistics show just how structural it is.

According to a 2025 national survey on violence against women by ISTAT, almost one in three women in Italy aged 16 to 75, meaning 31.9 per cent in about 6.4 million people, have experienced physical or sexual violence at least once in their life.

More than a quarter have been assaulted by someone outside the couple, while roughly one in eight women who have, or have had, a partner report violence within the relationship. Those numbers describe an ordinary landscape of risk that sits in stark contrast to the way television still treats many cases as extraordinary or exceptional.

How surveillance logic enters everyday life

Simona Sala offered a revealing example: the digital school register used nationwide to track grades, absences and behaviour. A system designed for transparency has gradually normalised continuous monitoring. This surveillance habitus, a learned expectation of being watched, often extends into romantic relationships, where sharing passwords or location data is framed as trust rather than control.

Much of Italian entertainment reinforces similar patterns: reality shows frequently turn jealousy or possessiveness into entertainment tropes, shaping how viewers internalise ideas of care, intimacy and authority.

Padula added that audiences detach emotionally as a defence mechanism, and that this detachment is reinforced by gendered language and linguistic framing that portrays women as unreliable, provocative or partially responsible for the violence they face. That symbolic order does not emerge only in adulthood.

An ISTAT survey carried out in 2023 among young people aged 11 to 19 found that over half of respondents agreed that physical appearance is more important for girls than for boys; about one in four thought men are less suited to domestic work; and around one in five believed boys are naturally more gifted than girls in science and technology.

Agreement with these stereotypes was higher among foreign-born teenagers and among those from poorer households or with less-educated parents, and consistently lower where mothers had a university degree. In other words, before they become media audiences, many young people are already learning to associate femininity with beauty and care, and masculinity with competence and authority. A pattern that news and entertainment later echo and amplify.

Italy’s National Council of Journalists tried to react to this in 2015 with its guidelines “Tutt’altro genere di informazione”, which call for accurate and non-stereotypical representation of women. The existence of such a manual signals how deeply rooted these distortions are.

Television’s long shadow over public perception

To understand the roots of these narratives, it is necessary to return to 1979, when RAI broadcast the documentary “Processo per stupro”. It revealed systemic victim-blaming in Italian courtrooms, where women were interrogated through questions like “How was she dressed?”, “Why was she there?”, or “Did she provoke him?”. These logics continue to shape contemporary reporting.

Later, the television programme “Un giorno in pretura” turned legal proceedings into a narrative format mixing intimacy, voyeurism and judicial drama, establishing a template that still influences public expectations of justice on screen.

Editorial decisions in television news broadcasts carry symbolic meaning. When a femicide appears mid-bulletin, it becomes routine crime news rather than a systemic issue. Crime reporting in Italy traditionally emphasizes sensational details and isolated events over structural contexts. This framing affects how the country understands violence: as an incident, not a pattern.

Online platforms as accelerators of old narratives

Digital platforms accelerate these dynamics. The recent shutdown of the Facebook group “Mia moglie” exposed how misogynistic communities function online. Members shared intimate images without consent, made jokes about violence and reinforced each other through male in-group solidarity.

Their comments often relied on moralistic judgment aimed at women, producing social isolation for the victims. Together, these mechanisms represent secondary victimisation, the additional harm inflicted when media or communities blame or discredit victims.

Even celebrity discourse becomes entangled in this logic. When television personality Belén Rodríguez said on Belve, “I used to beat up my exes,” the clip circulated widely online without context. Italian platform culture often collapses irony, confession and behaviour into a single undifferentiated register, fuelling ambiguity and spectacle.

What we choose not to see: the “shadow zone”

Monterosi’s idea of the “shadow zone”, the emotional space where jealousy, insecurity and rage accumulate, challenges one of the most persistent tropes in Italian crime reporting: the sudden, inexplicable “snap” or raptus used to explain femicides. Italian newspapers still rely on formulaic phrases such as “crime of passion,” “blinded by jealousy,” “he was a quiet man,” or “she wanted to leave him.”

The data tell a different story. Preliminary 2025 findings from ISTAT show that the majority of rapes reported by women are committed by someone they know intimately, most often current or former partners. Strangers account for only a small minority of cases.

At the same time, psychological and economic abuse within relationships affect a significant share of women, while only a small fraction of those who experience partner violence, roughly one in ten, according to ISTAT, report it to the authorities.

The familiar media figure of the unknown predator jumping out of the shadows is statistically marginal. The everyday reality of violence is much closer, and much less spectacular.

In 2023, writer Michela Murgia criticised the narrative structure that presents the killer’s own justification as an explanatory key to the crime. Research by Cominetti and Belotti in 2024 confirms that even when news outlets adopt feminist vocabulary, the underlying narrative remains largely unchanged.

Their study shows that coverage of the Cecchettin case did not represent a turning point. Instead, it intensified existing tendencies toward spectacle, platform-driven sensationalism and the instrumental use of feminist language as an engagement strategy.

Strappato’s intervention at WomenUp brought these tendencies back down to the level of lived experience. She reminded the audience that many women do not leave violent relationships when violence first appears, but when they feel their children’s safety is at risk.

Fear of not being believed, fear of economic repercussions and fear of losing custody coexist with low trust in institutions. ISTAT’s latest data suggest that awareness is slowly growing: more women identify what they have suffered as a crime and seek help from anti-violence centres and specialised services.

But the gap between lived violence and formal complaints remains wide. That gap is precisely where media narratives can either normalise or challenge the status quo.

So what should the media do?

Toward the end of the conference, speakers reflected on what journalists can do differently. Reporting should offer context rather than isolated updates, especially in a media environment where femicides often appear as a catalogue of cases.

Sensationalism and suggestive storytelling continue to distort public understanding, as shown by headlines like “He kills her with 36 stab wounds: she had another man,” which shift responsibility onto victims through implication alone.

Speakers also argued that entertainment cannot be treated as neutral. From Grande Fratello to daytime talk shows, television formats often reproduce sexist tropes and normalise forms of control. Newsrooms, they said, should make editorial choices visible, explaining why a story leads a broadcast rather than burying it.

And journalists should rethink their choice of sources: rather than interviewing neighbours who describe perpetrators as “an unlikely suspect,” they should prioritise experts, social workers, survivors and researchers.

Restoring complexity: a necessary cultural shift

Italy continues to live with a culture of control that stretches from digital childhood to the public gaze of television and social media. Indifference grows when stories lose context and spectacle replaces understanding. Violence against women is more than a recurring headline; it is a mirror of the society that produces it.

Until Italian media abandon the emotionalised grammar that blurs the line between information and entertainment, the country will continue to mistake visibility for progress.