Key Highlights

What makes Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar an unforgettable masterpiece is not only space travel or the complex astrophysics it translates into something visually graspable, but it's about what time does to love, family, and survival. Beyond the science, it reminds us that technology can take us far, but it cannot replace a home, restore lost years, or undo the emotional weight of choices. 'Interstellar'’s central question becomes urgent: When this planet Earth becomes unlivable anymore, are we meant to leave it, or are we meant to save it when we still have time? In the end, the universe stays vast and uncertain, but what remains constant is human responsibility, connection, and the decision of what we are willing to protect.

“Look at that brightest one near the Moon. That’s the Evening Star, Venus.”

On summer evenings during my childhood in the village, my grandfather, a retired mathematics teacher, would point towards the sky and name what he saw. Lying in the yard, watching constellations emerge from the darkness, the universe never felt distant or abstract to the little girl in me. Long before I understood astrophysics or relativity, my relationship with the cosmos began as a personal one, shaped by stories, memories, and human connection.

“And there,” he would add, “those seven stars in that pattern are Saptarshi Mandal (Ursa Major).”

The sky has always held a strange power over human attention. Across centuries and cultures, people have looked up and tried to make sense of what they saw, first through stories and symbols, and later through science. Astrophysics is the modern form of that same hunger for knowledge, one that has produced remarkable answers, while leaving an even larger ocean of questions still open. Some ideas are measurable and proven, while others remain theoretical, debated and explored but not yet confirmed. This tension between what we know and what we can only imagine often finds expression in art, manifesting in books, folklore, and science fiction cinema. Films like Contact, Gravity, Apollo 13, and The Martian show how space can be both a scientific frontier and a deeply human one, and Christopher Nolan’s 2014 masterpiece Interstellar stands among the most unforgettable.

For most of human history, the universe was understood through what could be seen and measured. Today, physics describes our reality through four dimensions: three dimensions of space (length, width, and height), and a simple fourth dimension we cannot see but live inside every moment. That is ‘time’. We experience time in ordinary ways: past and present, yesterday and tomorrow, years ago and years ahead. If space tells us where something exists, time tells us when it exists. Together, these form ‘Spacetime’: the idea that space and time are not separate, but deeply linked.

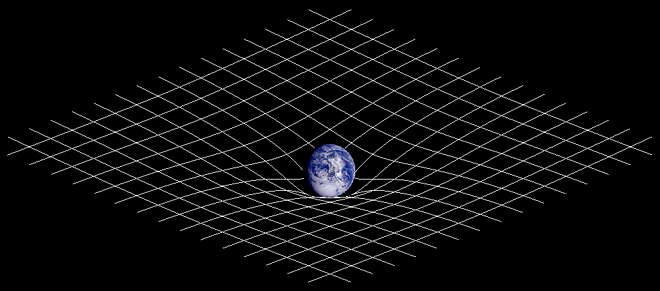

Think of Spacetime like a trampoline. A heavy ball (a planet) creates a dip. If you are in that dip, your 'clock' actually ticks differently than someone on the flat edge. This isn't just movie magic. It is Relativity.  A simplified view of spacetime curvature Image credit: Johnstone, via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0) |

Modern theoretical physics also suggests that these four dimensions may not be the full story. Some theories, including ‘String Theory’, propose that the universe could contain additional dimensions beyond what we can directly observe. These extra dimensions remain unproven and invisible to everyday experience, but they continue to shape scientific debate about how reality might be built.

It is within this gap between confirmed reality and theoretical possibility that science fiction finds its most powerful material. Interstellar uses that space to tell a story that feels deeply personal: survival, time, and responsibility, and what happens when time itself becomes unequal.

The Currency of ‘Time’: Why Physics Makes Every Minute Count

This is where Interstellar becomes more than a sci-fi film. It does not treat space as an exotic backdrop, but as a setting where ordinary human emotions are tested under extraordinary scientific limits. In Nolan’s universe, time is not just a ticking clock. It becomes pressure, distance, and irreversible loss. The film’s most haunting idea is simple: when time becomes unequal, love, duty, and survival are no longer measured equally for everyone.

At the heart of the film is a conflict that feels painfully familiar, even outside the realm of space travel. Earth is slowly becoming unlivable, and survival begins to look less like progress and more like desperation. With food shortages and failing crops, agriculture becomes the last lifeline, the root of survival that society underestimated for too long. At the same time, scientists and explorers are forced to plan the unthinkable: leaving Earth behind and searching for another planet where life can continue.

But the mission comes with a heavy human price. People have to walk away from families, children, and ordinary lives, carrying loneliness, anxiety, frustration, and regret. The film builds this tension not through speeches, but through consequences, showing what happens when scientific logic demands sacrifice, and the cost is not comfort or money, but shattered hearts and lost time that can never be recovered.

Time, in this film, is not fair. It stretches, slows, and steals moments in a way that feels almost cruel. And that cruelty becomes personal. It doesn’t just change the plot. It changes childhoods, parenthood, and the fragile thread of connection between people who love each other but cannot exist in the same timeline.

In most films, distance is the enemy. In Interstellar, time is.

One reason the film leaves such a lasting impact is that it takes a scientific truth, time dilation, and translates it into a human wound. Even if a viewer doesn’t fully understand ‘Relativity’, they understand the emotional meaning instantly: what if you leave for a short while and return to find that years have passed for the people you love? What if your child grows old while you remain the same age? What if the world moves on without you, not because it chose to, but because physics made it inevitable?

The film also refuses to present science as a clean solution. Space is not a glamorous escape here. It is the last option. The universe is silent, vast, and indifferent. And within that indifference, humans still carry their most fragile and stubborn qualities: hope, attachment, responsibility, and the desire to protect someone beyond themselves.

Beyond the Four Dimensions: Expanding Our Perspective on Legacy

In Interstellar, the fifth dimension is not presented as established science, but rather as a powerful concept derived from complex theories that physicists continue to explore. If time is the fourth dimension that moves us forward, the film imagines a fifth as a space where spacetime can be seen from the outside, like watching one’s own life as a film from a distant frame. Trapped there, Cooper, the film’s central character, is not chasing knowledge. His heart is chasing his daughter, Murph. He watches her life unfold, tries to communicate through the bookshelf, and even begs his past self not to leave Earth. The science remains speculative, but the emotion is unmistakable: time becomes a wall, and love becomes a desperate attempt to cross it.

Black Holes, Wormholes, and the Fear Behind the Science

Interstellar uses big scientific ideas like black holes and wormholes, but it never treats them as fancy space concepts. They become the reason the astronauts feel rushed, trapped, and terrified. In the film, the wormhole is depicted as a shortcut through space, a chance to find a planet that can support sustainable life. But it also feels like a one-way door. Once they enter it, they are stepping away from Earth and from the people they love, with no guarantee of return. Survival is not just about reaching another world. It is also about accepting that time may punish them for even trying.

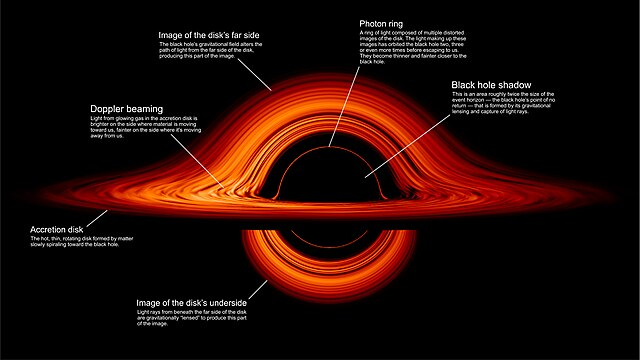

A black hole is a region in space where gravity is so strong that nothing can escape, not even light. We cannot see it directly, but we can detect it by how it pulls nearby matter and bends light.  A black hole’s accretion disk and 'shadow', where gravity bends light into a glowing ring Image credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Centre / Jeremy Schnittman (2019), via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0) |

A wormhole is a theoretical tunnel in spacetime that could connect two distant places in the universe, creating a shortcut for extremely long journeys. Einstein’s general relativity allows wormholes mathematically, but none have been discovered so far. Because they bend spacetime, wormholes could even act like time-travel pathways in theory, but that remains unproven.  An illustration of a theoretical wormhole, often described as a shortcut through spacetime Image credit: Adobe Stock | vchalup (licensed image) |

Back on Earth, Murph grows up carrying anger, confusion, and unanswered questions. But when she finally solves the gravity equation, her victory is not just scientific. It is emotional. It is the moment she realises her father never truly left her. The ‘ghost’ behind the bookshelf was always Cooper, trying to reach her from beyond ordinary time.

The Docking Scene: When Survival Demands Sacrifice

One of the most unforgettable moments in Interstellar is the docking scene. It is not just a technical sequence. It is panic, grief, and courage compressed into minutes. The spacecraft is spinning violently. The margin for error is almost zero. Everyone knows that one wrong move can end the mission instantly. In that moment, Cooper chooses to risk his own life to save the others and keep humanity’s last hope alive. It is a brutal reminder of what the film keeps repeating in different ways: survival is never free. It always demands a price, and often that price is paid in fear, loneliness, and the risk of never returning home.

From 2014 to 2026: What Science Changed and Why the Film Still Endures

With theoretical physicist and Nobel laureate Dr Kip Thorne guiding its science, Interstellar stands out as a rare blockbuster that treated astrophysics with seriousness.

When Interstellar premiered in 2014, it felt like a bold vision of what might lie beyond our solar system, rooted in real physics but still shaped by imagination. In 2026, parts of that vision feel closer to scientific reality, not as proof of the film’s fiction, but as progress in our understanding of the universe.

In 2014, even some of the film’s apparently most ‘real’ ideas still felt distant to the public and scientists. Gravitational waves were widely discussed in science, but had not yet been directly detected. That changed soon after.

In 2015, scientists made the first direct detection of gravitational waves, a breakthrough that reshaped modern astrophysics and later contributed to Kip Thorne’s 2017 Nobel Prize in Physics. For today’s readers, that timeline matters: Interstellar arrived just before a major scientific turning point, and the universe it portrayed began to feel less like imagination and more like an unfolding reality.

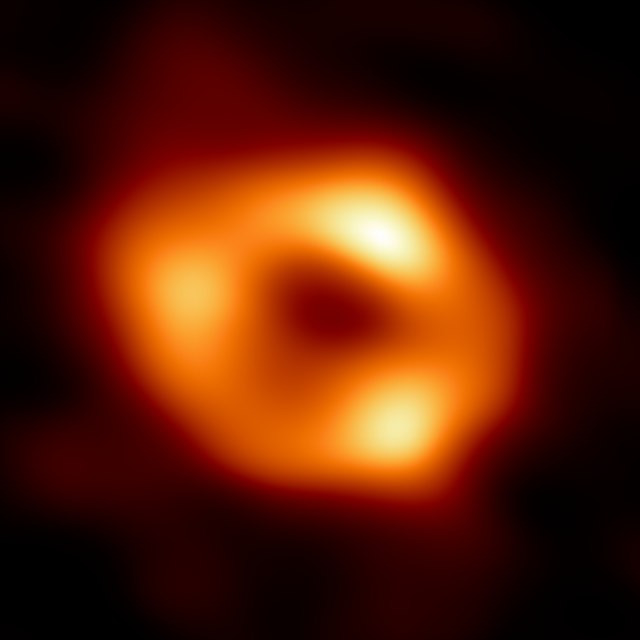

In 2019, the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) collaboration captured the first direct image of a black hole’s ‘shadow’, the supermassive black hole in the galaxy M87. Then, in 2022, EHT released an image of Sagittarius A*, the black hole at the centre of our own Milky Way. These achievements turned black holes from distant theory into visible evidence.

The first-ever image of the M87* black hole, captured by the Event Horizon Telescope in 2019 Image credit: Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration (EHT), via ESO / Wikimedia Commons |

First image of Sagittarius A*, the central black hole of our own galaxy Milky Way, captured by the Event Horizon Telescope in 2022 Image credit: Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) Collaboration, via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0) |

In the years that followed, gravitational-wave observatories such as the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO), Virgo, and Japan’s KAGRA have detected black hole mergers that ripple spacetime itself, reshaping scientists’ understanding of how black holes form and evolve.

Closer to the film’s emotional core, gravitational time dilation is not just a cinematic idea. Modern satellites and atomic clocks must account for it to maintain GPS accuracy, showing that time really does behave differently under different gravitational conditions.

The search for exoplanets has also accelerated in the past decade. Thousands are now confirmed, and missions like Kepler, TESS, and the James Webb Space Telescope continue to push the hunt for potentially habitable worlds: the very kind of question Interstellar dramatised as humanity’s last hope.

At the same time, not everything in Interstellar has moved from theory to reality. Concepts like wormholes and higher dimensions remain unverified and unobservable, even though they appear in serious theoretical physics discussions. The universe still offers a familiar mix: some answers gained, and many mysteries intact. That contrast is exactly what makes the film’s science feel honest; it separates what is measurable from what is still imagined, while keeping the human stakes at the centre.

In 2026, Interstellar’s warning about Earth does not feel distant. The film’s ‘agricultural blight’ may be fictional, but its anxiety is familiar: failing crops, climate stress, and the fear that human progress can collapse when nature stops cooperating. At a time when sustainability is no longer a slogan but a global necessity, Interstellar’s central question becomes urgent: Are we meant to leave Earth, or are we meant to save it? The film reminds us that while we have the technology to reach the stars, we do not yet have the technology to replace a home.

And while space missions like Artemis and long-term discussions about Mars continue to grow, the film reminds us of a quieter truth: reaching the stars is not the replacement of our own home!

This is why Interstellar still endures in 2026. The film did not ‘predict’ the future. But it captured something more lasting: science advances in steps, while human emotions remain constant. Even as knowledge expands, humans continue to struggle with duty, sacrifice, and the fear of losing what matters most.

The Interstellar Mindset for Daily Life

Interstellar’s story may travel through black holes, wormholes and search for sustainable planets, but what it finally returns to is something far more familiar: the way ordinary human life is shaped by time, choices, and responsibility. That is why the film still feels personal, even when its science feels distant.

When I think back to those village evenings under the stars, with my grandfather calmly naming constellations, I realise the universe did not feel like a puzzle to be solved. It felt like a presence of something very close to the heart, something vast, quiet, and humbling, but also strangely intimate. That childhood feeling becomes the emotional backbone of Interstellar, too: space is not just a place to explore, it reminds us what finally matters.

1) Perspective: The Universe Makes Us Smaller, But Not Meaningless

Interstellar reminds us that our problems may be tiny compared to galaxies and the vast, unresolved mysteries of the universe, but our actions are not tiny. In an indifferent universe, what still matters is what humans (like Cooper in the film) choose to do for each other. Cooper’s journey is not heroic because he travels far through space; it is heroic because he carries the weight of love, guilt, duty, and sacrifice through every decision.

2) Time: The Only Resource We Can’t Earn Back

The film’s most painful lesson is also its most practical one: time is not just a clock; it is a non-renewable resource, it is a cost. On the Earth-like planet found at last, time moves differently, and the characters pay for it with years they can never recover. For the viewer, science becomes a reminder that, in real life too, time is that one currency we spend daily without noticing.

Not every loss looks dramatic. Sometimes it is simply missed conversations, delayed apologies, postponed visits, and the quiet distance that grows when we take things and people for granted, assuming there will always be ‘later’.

3) The Physics of a Heartbeat

When we see the wormhole in Interstellar, we are not only seeing a shortcut through space; we are seeing a scientific ‘bridge’ for human intent. In 2026, in theoretical physics, ideas like spacetime ‘bridges’ are still discussed, mostly on paper, not proven in reality.

The wormhole symbolises human urgency, the desire to reach what matters before it is too late. For the viewer, the value lies in the metaphor: how often we search for shortcuts in life to outrun discomfort, delay, or responsibility, only to realise that the long way- the presence, the waiting, the staying, was the only path that truly mattered.

4) Legacy: What We Leave Behind is Not Always Technology

Interstellar also suggests that survival is not only about escaping Earth. It is about what we carry forward as a species: knowledge, courage, and care.

In the film, the bookshelf is more than a plot twist. It represents the sum of human knowledge passed from father to daughter; it becomes a quiet symbol of inheritance, how one generation tries to pass meaning to the next, even across distance and time.

And perhaps that is the most 'Interstellar' idea of all: that long before we become a spacefaring civilisation, we must learn how to value the people beside us, while we still share the same sky.

Conclusion: What the Film Ultimately Asks of Humanity

In the end, Interstellar is not remembered only for its visuals, its music, or its scale. It is remembered for what it makes people feel about TIME. It turns the universe into a mirror, reflecting not just scientific mysteries, but human priorities.

For all its astrophysics and cosmic ambition, Interstellar ultimately returns to something simple: the universe may be vast and unknowable, but the human heart still measures life in moments, connections, and responsibility. Science may change what is possible. But humanity decides what is worth saving.

The ‘Interstellar’ Checklist: 5 Things to Notice in Your Next Viewing |

The Silence: Notice how sound doesn’t travel in the vacuum of space; the film often lets silence speak, staying true to scientific reality. |

The Clocks: Listen to the ‘ticking’ soundtrack on the water planet, where each tick occurs every 1.25 seconds. In the film’s time-dilation math, that translates to 21.25 hours on Earth, just two and a half hours less than a full day on Earth. This score turns itself into an audible countdown of lost time, turning time into something anxiously heavier. |

The Docking Scene: Watch how survival under immense pressure becomes a matter of seconds, where courage and precision decide the future of the mission, and eventually, humanity. |

The Bookshelf: It represents the sum of human knowledge passed from father to daughter, and the desperate need to communicate across time. |

The Video Messages: Observe how time turns into emotional loss, as love continues, but life moves forward without waiting. |