Listen to the Article

Key Highlights

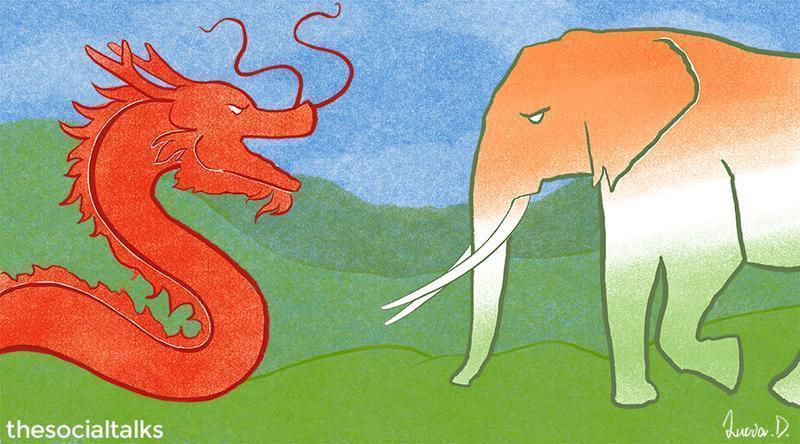

In April 2025, marking the 75th anniversary of diplomatic ties, Chinese President Xi Jinping proposed a "Dragon-Elephant tango" to symbolize harmonious relations between China and India. This gesture follows the October 2024 border patrol agreement aimed at de-escalating tensions after the deadly 2020 Galwan Valley clash.

A Foundation of Mistrust

The Dragon-Elephant tango metaphor dates to 2011 when TIME magazine used it to compare India's rise to that of China in one of their cover stories. India and China have shared a long-standing and often turbulent history. A foundation of mistrust was created not long after India gained independence. It took decades of diplomatic attempts to mend the bilateral ties between China and India after the Sino-Indian War in 1962. A region of Ladakh known as Aksai Chin was militarily captured by China and solidified its hold on it after the Sino-Indian War in 1962. Although Aksai Chin is currently administered by China, India asserts that it is a part of Ladakh.

At the Line of Actual Control (LAC), military tensions have persisted despite continuous trade and economic interactions. China has attempted to apply pressure along the border with military incursions in Depsang (2013), Chumar (2014), and Doklam (2017), according to Lt. Gen. DS Hooda (retd). He asserts that the 2020 Galwan violence in Eastern Ladakh was a total surprise because the trade engagement and diplomacy were meant to deter China from using military force. Hopefully, the four-year deadlock that followed showed that India will not bow to pressure. However, he contends that India must enhance its military's capabilities.

Image Source: Open Street Map

Tensions decreased after the Sino-Indian agreement on patrolling arrangements in October 2024 almost four years after the 2020 Galwan clash between Indian and Chinese troops near their shared border in the Himalayas. The presidents of China and India congratulated one another on the 75th anniversary of the start of their diplomatic ties in April 2025. Xi Jing Ping compared the relationship between China and India to a "Dragon – Elephant Tango" between their respective symbolic animals.

Geopolitical Chess: Trap or Tactical Leverage?

Although India recognises that a completely benign relationship with China is possibly not achievable, it nevertheless strives to maintain strategic stability. According to Lt Gen Hooda, India has leverage in this situation because of its expanding market, growing diplomatic influence, and powerful military that cannot be forced at the border. In support of this, Lt Gen Rakesh Sharma asserts that, particularly considering China's recent tariff war with the US, India does possess the trade leverage and consumer market that China needs. Notably, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has forecasted India's real GDP growth at 6.5% for both 2024/25 and 2025/26 driven by private consumption and economic stability. Plus, China and India participate in many international fora which provide China with credibility and a global voice. Such factors collectively enhance India's position in its strategic engagements with China.

Firstpost claims that since China's strategic calculus aims for a hospitable boundary and a subdued neighbourhood, marginalised India fits in well with its grand design and that no real policy change can be anticipated.

Given their shared border and extensive trade ties, India has little choice but to engage with China. The unsettled border is a potential flash point, as witnessed after 2020. However, there will be no tango. There are fundamental strategic issues that will ensure an element of rivalry between India and China. China views India as increasingly moving into the US camp to contain Beijing. India sees Chinese inroads into South Asia as encroaching on New Delhi's sphere of influence. These differences are likely to sharpen in the future, predicts Lt. Gen DS Hooda (retd).

Diplomacy vs. Deployment: Reading China’s Mixed Signals

Building on Lt. Gen. Rakesh Sharma's observation China's military operations especially in Eastern Ladakh and the larger Himalayan region are based on established strategic doctrines rather than being haphazard manoeuvres. These measures are an extension of a security-focused strategy that has mostly not changed since the People's Republic of China was established. The Chinese Communist Party (CPC) operates under a highly centralized organisation where real authority belongs with the Politburo Standing Committee (PBSC) and the Central Military Commission (CMC) not with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs or the State Council.

According to this framework, Chinese diplomacy which is frequently carried out by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs or the State Council functions more as a communication instrument than a decision-making one. It has no power to change military posture or strategic objectives but it can provide cooperation frameworks, such as the "Dragon-Elephant Tango" to manage tensions. These are decided by the PBSC, the highest level of political leadership that establishes the general direction of China's national strategy and the CMC which directly supervises the People's Liberation Army (PLA).

India must therefore approach China's outreach with the knowledge that inside China's political structure, military and diplomatic initiatives come from different baskets. The military's actions clearly show China's continued border assertiveness especially in regions Beijing views as essential to its sovereignty and regional influence even while diplomatic discourse may promote peace harmony or tango-style cooperation.

China’s Influence in India’s Neighbourhood

China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has led to significant investments in South Asian countries but it has also triggered concerns over its influence on India’s neighbourhood. For example, after failing to pay Chinese debts Sri Lanka has leased the Hambantota Port to China for 99 years. The development of Gwadar Port in Pakistan and Pokhara International Airport in Nepal both of which received significant Chinese support have raised concerns about these countries' long-term economic sovereignty. These developments have prompted India to reassess its regional strategy and strengthen its own diplomatic and economic ties with the area. India is forming its own strategic arc as China uses economic influence to infiltrate its own territory.

India in the Indo-Pacific: Long-Term Stakes and Strategy

It is also crucial to assess India's standing and implications in the Indo-Pacific region when discussing regional influence. With a 2000-kilometer peninsula in the Indian Ocean and 60,000 ships navigating through it, experts say India has a major geographic advantage. Although India maintains positive connections with countries in the Indo-Pacific, Lt. Col. JS Sodhi believes that it needs to be more economically and militarily prepared.

To enhance its strategic depth and secure its maritime interests, India has established port access and defense ties across the region. The establishment of strategic and naval connections with nations such as Singapore (Changi Naval Base), Indonesia (Sabang Port), Oman (Duqm Port), Seychelles (Assumption Island), and Iran (Chabahar Port) in order to protect its maritime interests and thwart China's expanding influence. This growing network of maritime partnerships is also a response to increasing Chinese activity in the region. Needless to say, India and China will continue their long-standing strategic competition. The PLA Navy may pose a threat to India's hegemonic position in the Indian Ocean as its capabilities increase and its presence in the region is anticipated to rise over the next several years.

India’s broader multilateral engagements further reflect its vision for the region. India's dedication to an open and free Indo-Pacific is demonstrated by its involvement in the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) which it shares with the US, Japan and Australia. India must however, balance maintain strategic autonomy and avoid overt alliance with any bloc that counters China's ambition. In an effort to stop China's growth in the South China Sea, the Philippines recently encouraged India to join a proposed "SQUAD" alliance that would include the US, Australia, Japan and even South Korea. Amid these dynamics, new proposals for deeper alignment continue to emerge.

Conclusion

The Dragon–Elephant metaphor may suggest elegance and coordination but the reality of India–China relations is far more complex. Behind this apparent warmth lies strategic mistrust, competitive aspiration, and historical grievance, forging a long-term rivalry. In this waltz, India ought not to be complacent. And while new developments unfold between Beijing's outreach and posturing, New Delhi should remain prepared to act independently, strengthen its alliances within the region, and be braced for if this dance devolves into a duel.

Acknowledgments

I am deeply grateful to Lt Gen (Dr) Rakesh Sharma (Retd.), Lt Gen Deependra Singh Hooda (Retd.), and Lt Col JS Sodhi (Retd.) for graciously sharing their valuable time and insights. Their perspectives, shaped by decades of service to the nation, have been invaluable and carry immense depth and credibility. Their contributions have been instrumental in enriching this article with strategic clarity and nuance.