“Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears”… Art and Propaganda to be uneasy bedfellows is more impulsive and emotional an idea than logically reasonable. The changing psychology of the Roman mob persuaded by Brutus and Mark Antony, equally playing their propaganda roles provides the masterpiece of an example to let understand the power as well as the twain perspectives. And there exists the scholarly idea of the greatest speech in history to be made “iff” at the presence of the greatest orator ever seen, perhaps talking about Pericles or Demosthenes himself, the outcomes of Mark Anthony’s speech would have been scraped out of the history. That is what art does. Carve something or scrape it away.

The image of Hitler focussed and determined at a future which is only visible by him. He is depicted as a flag bearer, and not the emperor thereby diminishing the opinion of self-proclamations. And the inscription reads: "Whether in luck or unhappiness, whether in freedom or in prison, I have remained loyal to my flag, which is the state flag of the German Reich today."

Some centuries after the great Egyptian civilization, minister Goebbels took to extremes the concept of propaganda redrafting the idea to be a bad one. Look at the fact that Tutankhamun, the boy-king was just mediocre amongst the line of kings who ruled this planet. Apart from the golden-tinted nature of his society’s wealth and pyramids, what else does it make him an important historical figure? But still, the propaganda to portray him as a god-king and a civilization as prosperous was successful. On a second thought on Picasso's idea of a hypothetical scenario where art would be given the keys to a city, “If art is ever given the keys to the city, it will be because it’s been so watered down, rendered so impotent, that it’s not worth fighting for,” people consider art as a substance deprived of intentions and agendas. But later we understand it to be such with varied multitudes of artistic skill. Just like the cathartic or didactic effects expected from art, or various similar expectations propaganda is also one of them. The term propaganda is not a noun but a verb that means propagating and not propagation in modern Latin. This is where despite the popular belief of art being impotent, there arouse l'art pour l'art or the Art for art’s sake.

Is Propaganda Art Great Art?

Obelisks, Pyramids, coins, statues, etc., have always been a part of political art. And not all political art is automatically propaganda. But the question of how propaganda art can be good art is compartmentalized. The Guernica, an exemplary piece of art throughout time is often considered a work of propaganda. Understanding all the material facts that surround a particular art leaves us with two perspectives. Either to understand it for the meaning it holds, or as we said l'art pour l'art. But what is the point in blinding out the fact that the art is not just an artistic expression but also his political expression that produces propaganda? Isn’t two better than one? When Picasso withheld the painting from reaching Spain until the fall of the Franco regime, he made it the statement of his revolt against the bombing in the Basque town of Guernica. When the world looks at Guernica for its artistic marvel, it also contains propaganda. Moreover, it doesn’t stop there. The close resemblance of Mary Magdalene to the figure in the lower right and its resemblance to the Isenheim Altarpiece provides the insights to a broader observation that perhaps all artistic expression ever to have created is a piece of propaganda. The Ten Commandments and the seven miracles of Jesus which are often painted throughout churches are propaganda. With this idea, we cannot shake away the notion that the Baroque, and later renaissance pieces of high art are also, but propaganda. So can propaganda produce great art? Yes.

Manipulation by Design

A large portion of the history-savvy population consumes the word 'propaganda art' with the world war posters, Nazi and Hitler-themed cut-outs, and oppression. Propaganda became a word thrown around a lot during the 1900s to 1950s. The oppressors and the oppressed found art a more powerful form of expression, and this was adapted into its regional varieties based on the purpose. Two styles of propaganda art approaches can be categorized. First of it was the direct-to-appeal designs such as the famous Kitchener’s, the citizen-soldier, and the family, children, and living room scenes which were used to instigate the common into standing (or act upon) for the greater good of the society. Secondly, designs that portrayed the loss and helplessness of a party in demeaning the public image of the opposition. This was often done with the use of satirical propaganda. In such cases, for example, a famished person can be placed at the top, a powerful place, where he can influence the wealthy fashion industry and in turn the whole world who is pleading to sacrifice food and stay in shape.

The American version was adapted from the British.

India after the 1930s

Credits: National Army Museum, London.

On September 3, 1939, at 8:30 pm, the then viceroy of India Lord Lithilingow announced the British Empire to be at war with the Germans, and as a colony to his Majesty’s Government, Indians are obliged to participate in it. Hearing this on all frequencies through the All India Radio, the Indian National Congress was shocked upon this disgrace to India’s dignity. India did have supplied Britain with her soldiers in the previous war but now the situation was different. Meanwhile, the Japanese who understood the rising importance of India in the Asian context and started propaganda posters and works that were instigated against the British. They were serious about their efforts, such that when Sikh soldiers were captured, they were given options to either join the Indian Independence League or face the greater consequences, which sometimes was execution. Journalist and writer Raghu Karnad in his In Farthest Field: An Indian Story of the Second World War, writes on how the city of Rangoon after it falls to the Japanese, became showered with “thousands of fluttering leaflets. These were propaganda cartoons…depicting starving Indians ground under the heels of fat imperialists or turbaned jawans being kicked out of the evacuation lorries by blond-haired Tommies.” They even had these posters fluttered down on battlefields in Europe, North Africa, and Burma, to psychologically convert Indian soldiers. Some posters depicted alternate outcomes if India got its freedom.

A woman, perhaps the embodiment of Mother India, is holding a dying man in a sea of bodies at the Jallianwalah Bagh massacre, 1919. The text in Hindi and Bengali reads, “Any Indian whose blood doesn’t boil at the memory of the Amritsar massacre cannot be called an Indian. This is the golden opportunity for revenge.” Credits: National Army Museum, London.

Credits: National Army Museum London.

But even though this was a healthy effort for the Japanese – The Nippon, the British had printed and spread ideas in their favor explaining their loyalty to Indians and Burmese which were their precious colonies.

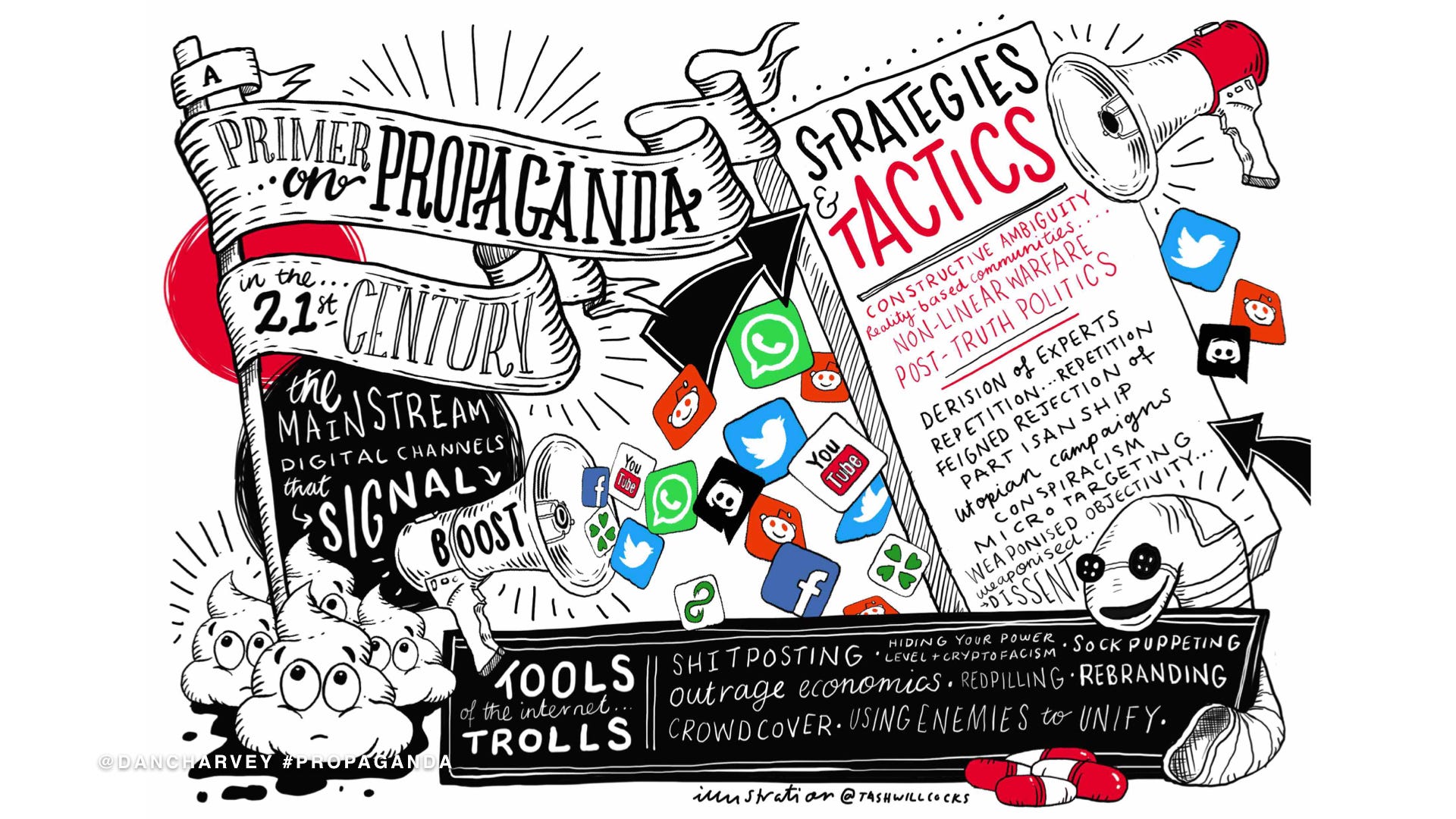

Post Modern Propaganda

With age, the medium of art and propaganda has changed. It would be an improper scale to measure the propaganda beneath an art form without considering various modern social theories such as political correctness, feminism, and the satire of the meme, etc. People today have various insights into how to evaluate art. The artistic quality of the art is highly subjective in the present day than it used to be. When a person opines his dislike for an artwork a huge population considers as a masterpiece, it can be justified. In a time where people have rather become active participants in judgment, rather than being passive as in the cases we have discussed, misinformation is a term sometimes the same and not the same, with propaganda. When a movie is depicted with its historical facts wrong, it can either be considered as misinformation or as satirical propaganda.

When people have opinions over topics far from their reach, great art becomes that which engages people.

Cover Photo: Shepard Fairey - OBEY.