Key Highlights

Since it became operational in 2002, the Delhi Metro has benefited a large number of people and has proved crucial for travel for those residing in Delhi as well as for people coming to the city for various purposes such as education and employment. However, along with its expanded connectivity and convenience, it also poses a few challenges for commuters, especially those belonging to lower-income groups.

On the busy evening of 25th August, Riya, a college student, heard the news of the Delhi Metro fare hike, effective from the same day. The first thought that comes to her mind is the extent to which her expenditure will rise. For us, it may be a marginal rise of Rs 150-200, but not for her. Next, she asks herself, can she travel by bus? Perhaps not, as she’s new in the city and completely unaware of the dense bus network of the city. Then, what can she do to keep her expenses within the limit? This is not just the struggle of Riya, but of many students and people who are struggling in the capital city to build a meaningful life for themselves and their families.

This article examines the Delhi Metro’s convenience and affordability from the perspective of daily riders belonging to middle- and lower-income groups. The story examines how often students studying in colleges in Delhi use the Delhi Metro to commute daily from their residential places to college. Along with that, it will also cover how convenient non-Delhiites find Delhi Metro when they travel for the first time in terms of ticket counters, boards, and signs mentioned in the metro station to guide commuters, the behaviour of metro staff, the DMRC card, and the DMRC app. It will also highlight how the increase in metro fare has affected the monthly budget of daily commuters who have a limited budget to spend on travelling.

Delhi Metro at a Glance:

The Delhi Metro is often described as the lifeline of New Delhi, the capital city of India. It’s the largest rapid transit system in India, connecting Delhi to the National Capital Region, including Gurgaon, Faridabad, Ghaziabad, Noida, Bahadurgarh, and other satellite cities. Delhi Metro connects these distant locations through its network of colour-coded lines spreading across and around the capital and surrounding regions. These lines include different colour-coded lines such as the Pink line, Blue Line, Yellow line, etc. The Delhi Metro spans more than 394 km across 8 cities with 285 operational stations.

It is operated and managed by Delhi Metro Rail Corporation (DMRC), a public sector company established by the Government of India and the Delhi Government in 1995. The first phase, Red Line, of the Delhi Metro was inaugurated on December 24, 2002, by then Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee. It started with just 39 km and 29 stations in its initial phases in 2002. Recently, at the start of 2025, its fourth phase extension was inaugurated by PM Narendra Modi, laying the foundation stone for additional extensions in the Red line.

Indeed, the Delhi Metro has undergone rapid development in expanding its network and reaching different cities around the capital, while the metro connectivity of other countries expanded at a much slower pace, despite starting much earlier than Delhi. During his 2022 visit to India, Japanese Ambassador Hiroshi Suzuki said he was surprised to learn that the Delhi Metro had expanded faster than the Tokyo Metro over the last 20 years of its operations. The London Underground began decades ago in 1863; it’s the world’s oldest metro and comprises 400 km with 272 stations in 2025. While the London Underground has been larger for more than a century, the Delhi Metro has expanded at a fast pace and now seeks to overtake it as one of the world’s longest metro networks.

The Delhi Metro was introduced in the city to ease traffic congestion in the capital city, combat air pollution due to congested vehicular traffic, and also provide alternative yet affordable and convenient options to the daily commuters in the capital city. Since Delhi attracts daily-wage migrants, job-seekers, and students from across the country in search of better employment and educational opportunities, the city witnesses constant movement throughout the day. The economic and social status of such people varies widely.

Thus, the city needs an affordable, pocket-friendly, and eco-friendly mode of transportation. Other modes of transportation in the city, such as bus services and Uber/Ola, have their own challenges. They are either not a safe option, especially for women, as they lack a fixed time of arrival like bus services, or have extravagant costs like Ola/Uber and cab services, which are nearly impossible to afford daily for even the middle class of society. This makes the situation even more difficult for daily-wage earners.

Reportedly, the Delhi metro was built on loans and tax breaks. Nearly 60% of Metro’s Phase I funding came from concessional loans, mostly from JICA. Later, DMRC clarified that this was a reason they are in debt, could not afford fare concessions, and the fare hike is also aimed at repaying those debts.

Delhi Metro — the second most unaffordable in the World

A 2018 study by the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) reveals that the Delhi Metro is the second-most unaffordable in the world, among the metros that charge less than a US dollar for a trip. It was based on data from the USB report on Price and Earnings, 2018, besides other sources.

The study further finds that after 2017’s hike in metro fare, the average commuter in Delhi spends 14% of their household income on daily Metro travel for work, after Hanoi, the capital city of Vietnam, where daily commuters spent 25% of their income. For 30% of Delhi riders, the percentage of income spent on daily commutes was as high as 19.5%. The study also claims that the fare hike has led to a 46% drop in ridership. The study also notes that while ridership was projected to reach 39.5 lakh in 2018, the actual figure was only about 27 lakh.

It further highlights that 30% of Delhi Metro commuters have a monthly income of Rs 20,000, which directly leads to the increased fare to 19.5% of their income on metro travel only; the last-mile connectivity will also be further added to this cost. Globally, up to 15% of income is spent on transport modes as affordable. The bottom 20% of households should not spend more than 10% of their income on transport. Contrastingly, in Delhi, nearly 34% of the population stands excluded from basic non-AC bus service because of its unaffordability.

However, the DMRC outrightly denied these claims and said that the study was selective as it only compared metros with smaller networks of the countries. The Delhi transport commissioner justified the fare revision and said that if they don’t increase fares, the quality falls.

Affordability of Delhi Metro — A Common Man’s Perspective

A third-year Delhi University student travels daily from Ghaziabad to her college in New Delhi. She belongs to a lower-middle-class family, where her father is the only earning member in the family, and she also has a brother, who is preparing for his master's. Every day she spends 90 rupees on her travel to college, while before the price hike in August 2025, this cost Rs 82. She explains how this 8 rupees of added everyday expenditure is affecting her budget, as it totals to Rs 200, additionally, in a month. She adds that though the increment is marginal, even a slight increase in expenditure affects her family’s spending and saving pattern, as she has a family of four, and only one person is earning.

Another student is pursuing her master's in Zoology from Indira Gandhi National Open University. She resides in Central Delhi, and due to her practicals, she has to travel daily for a month to her centre in Gurgaon. She also spends daily Rs 90 on the metro only; the fare of last-mile connectivity further adds to her restricted budget. She shares that she took admission in IGNOU due to low fees, and avoided daily commute, because the institute doesn’t require students to attend classes daily, and provides remote studying. But to perform practicals as a science student, now, she has to travel to college for a month, and then, for her theory examinations.

Notably, these fares apply to Smart Card users, who receive a 20% discount (10% discount on every ride + an extra 10% during off-peak hours). Those who don’t use smart cards as provided by Delhi Metro, the same distance of journey costs more to them. The journey from Gurgaon Millennium City Centre to Durgabai Deshmukh South Campus, for those who have a Smart card, costs Rs 44, while those who don't have one and buy tickets from the counter pay Rs 54 for the same distance.

Similar budget constraints affect many people, not just students, but also office-goers who must manage their monthly travel within a fixed amount. As Delhi has people who have shifted to the city from their hometowns in place of better jobs and educational facilities, they have to look after other major expenses, such as house rent in a costly city. Prominent universities in Delhi attract students from across the country each year because of the quality of education they offer. Many students come from villages and low-income families, live in rented accommodation, and find the additional transportation cost to be another significant challenge.

The DMRC has hiked its fare, which became effective on August 25, 2025, after the fares were set in 2017. Before the hike, the minimum fare was ₹10, and the maximum fare was ₹60 for normal travel days.

The revised fare of the Delhi Metro after August 2025:

Distance (in KMs) | Fare (Monday to Saturday) | Fare (Sunday & National Holidays) |

|---|---|---|

0 - 2 | Rs 11 | Rs 11 |

2 -5 | Rs 21 | Rs 11 |

5 - 12 | Rs 32 | Rs 21 |

12 - 21 | Rs 43 | Rs 32 |

21 - 32 | Rs 54 | Rs 43 |

More than 32 | Rs 64 | Rs 54 |

Credits: delhimetrorail.com

The fare of the Delhi Metro before the hike:

Distance (in KMs) | Previous Fare (Weekdays) |

0 - 2 | Rs 10 |

2 - 5 | Rs 20 |

5 - 12 | Rs 30 |

12 -21 | Rs 40 |

21 - 32 | Rs 50 |

More than 32 | Rs 60 |

Metro Concession Pass: The Students’ Demand & Student Parties Manifesto

For the last few years, the most talked-about point in the manifestos of student political parties in the University of Delhi has been the ‘Metro Concession Pass’. It’s a long-standing demand by students of colleges in Delhi, including Delhi University, Jamia Milia Islamia, Jawaharlal Nehru University, and many others, so the student leaders added it to their manifesto, and, election after election, promised to provide it to students.

The metro concession pass is supposed to potentially offer significant relief (up to 50%) to ease student commuting costs; more specifics are yet to be clarified, as this topic is discussed during campus elections only. It aims to reduce the high monthly travel costs, which range from Rs 1,800 to Rs 3000 for students, and allow them to invest it further in education and skills, also to allow easy commuting for those students who have financial challenges.

The fact that the metro concession pass is such a sought-after topic during student elections in Delhi colleges makes it evident that the Delhi Metro fare is unaffordable and poses financial challenges to students to commute daily to colleges.

The issue is simple with the bus and the metro travel. Students pay just Rs 75 for five months of unlimited bus travel in the city, but a single metro ride costs around Rs 40, which students with financial challenges cannot afford. Students even led protests for a Metro concession pass. During one such protest, Students' Federation of India (SFI) President, Sooraj Kumar, highlights that “it’s clear how threatened the authorities are by students, as they are even blocking our demand for something as basic as a metro pass.” Over 60,000 students signed the campaign for a concession pass.

In the 2025 Delhi University Student Union (DUSU) elections, RSS-backed student political party, ABVP, promised in their manifesto to ensure that metro concession passes are issued to all the students. ABVP won three out of four seats in DUSU elections. Following this, the Chief Minister of Delhi, Mrs Rekha Gupta, says that she will fulfil the long-pending demand of DU students to get their metro concession pass. But by the end of 2025, no such signs will be visible to students for the metro concession pass.

Over the last decade, every year, student leaders and parties led by national political parties like Congress, RSS, and AAP mention the metro concession pass during election campaigns, but it has become a topic to be raised during elections only, and remains an unfulfilled promise after every Union tenure, according to the students of DU.

Additionally, the challenge of last-mile connectivity also persists while travelling. One student shared that auto-rickshaws charge Rs. 20 per person for a distance of just 1.5 km. He shares, his college is at a distance of 1.5 kms from metro station, most of times the students walk to the college and also come back to metro station back by foot, but at times when are running late or they have their exams or practicals, they have to take auto, and he shares it costly for them to take auto every time. He added that a shuttle service run by the Delhi Metro or the Delhi Government for last-mile connectivity would be extremely helpful.

Delhi Metro’s Convenience — Riders’ Perspective

Every year, Delhi Metro caters to around 6.7 million passengers daily on average on weekdays. Though the metro is a cheaper, safer, and more comfortable option compared to other modes of transportation, it also poses challenges to commuters while allowing them to travel to their workplaces or other destinations. Commuters often struggle with last-mile connectivity, overcrowded platforms at stations such as Rajiv Chowk, Dilli Haat, Sarojini Nagar, New Delhi Railway Station, Hauz-Khas, etc, placing their luggage on X-ray belts during rush hours, and tracking their Smart Card balance after recharging at station machines.

One of the Delhi metro commuters who frequently travels to Gurgaon, first on the Pink line, and then interchanges to the Yellow Line, shares how once her Smart Card recharge in the metro station didn’t reflect in her card's total balance. She says earlier she used to recharge her Metro card online through the DMRC app, but after recharging for an amount of Rs 200 through the DMRC app, the balance was never credited to her Smart card, but was deducted from her bank account. Later, she complained about the issue to the Customer Care helpdesk in person at metro stations, where they said the amount would be credited back to your bank account if the recharge is not successful. She also showed the payment details through transaction history, but even that didn’t help her, and her Rs 200 never recovered.

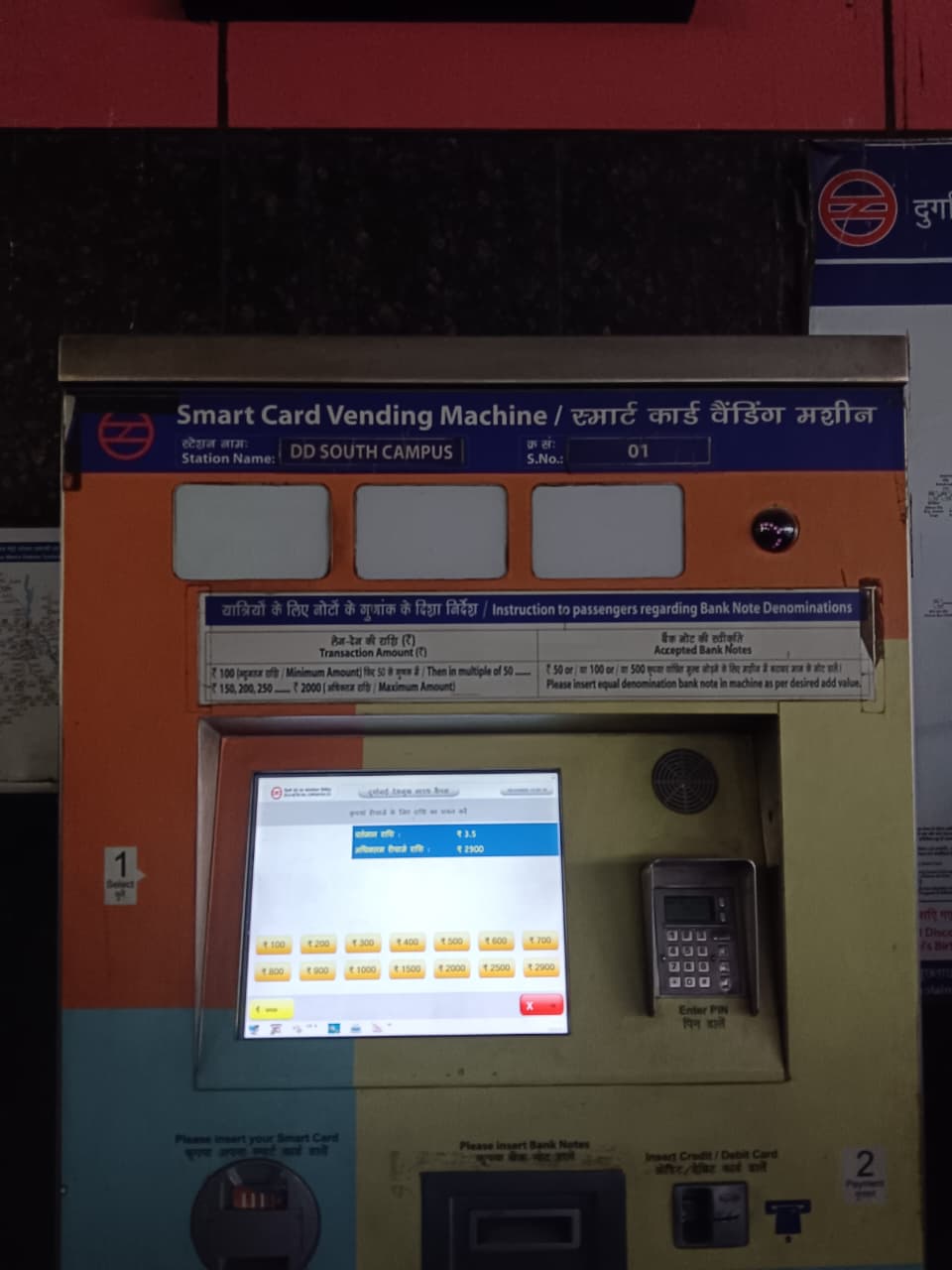

She shared another incident where she opted to recharge her Metro card through the Automatic Smart Card Recharge Machine in a Pink-line Metro Station, and inserted a Rs 500 note into the machine for the recharge. Following this, once again the amount wasn’t added to her Metro Smart Card, but this time Metro customer care officials verified the payment with a receipt, and when she asked for her money back. They didn’t immediately help her, argued, and tried to let go of the matter. Since she was adamant about getting her money back, they opened the machine and gave her the amount back. It took her 45 minutes just to get her money back due to the glitch in the machine, and this led her to waste her crucial time, as she was heading to very important work.

In another incident, another metro commuter shares that every time she travels to the railway station to catch a train for her hometown, she struggles to put her heavy bags inside the metro luggage X-ray machines. She shares her experience that in every metro station, there is a different body screening passage for men and women. But the X-ray machine remains common, and while travelling, when metro stations are overcrowded, she finds it very difficult to wait for her turn so that she can put her heavy luggage inside the machine.

During peak rush hours, the metro stations such as Rajiv Chowk, Delhi Haat, and Sarojini Nagar gets extremely crowded. The metro passing through these stations is usually so crowded that there is not even space for people to board the metro. People often find it difficult to breathe in the metro coaches due to their excessive overcrowding, and also because metro coaches remain sealed due to air-conditioning, shares another metro rider, who is claustrophobic.

For first-time metro users, the colour-coded lines, coloured floor markings, and bilingual signboards at every station helps and guide them through interchanges and platforms. The first-time travellers of Delhi Metro shared that they found the metro staff helpful, and the helpdesk was functioning all the time for customer services. The metro staff have been very vigilant in guiding them or solving their queries inside the metro station. Regular users also expressed appreciation for the constant availability of staff at Delhi Metro stations. This highlights a significant point of convenience for non-Delhiites in comparison to navigating a dense bus system.

The Big Picture Impact

In 2011, the United Nations certified the Delhi Metro as the world’s first railway project eligible for carbon credits for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. According to a study by The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI), by using the metro rail for travel in place of a road vehicle, a passenger saves about 32.38 grams of CO2 per kilometre.

Some commuters also raised concerns about physical QR paper tickets. Delhi Metro used to give plastic tokens to people to scan at the entry and exit of the platforms. These tokens were reusable. But paper QR tickets cannot be reused immediately and are less environmentally friendly. Some people don't travel in the metro frequently, thus don’t have a Metro Smart Card, and buy QR tickets at the counter. The paper-based QR tickets reduced the use of plastic by eliminating traditional plastic tokens. However, people can also book their online tickets, known as an app-based QR ticketing system, through the DMRC app, WhatsApp or other apps, and use e-tickets to reduce paper usage.

Thus, indeed, Delhi Metro is a lifeline of Delhi transportation, but it also has its own shortcomings with respect to commuters. For college students, most of the time it gets inconvenient and unaffordable due to fare hikes, lack of a concession pass, and last-mile costs, despite it being one of the safest and time-efficient options. For non-Delhiites and low-income commuters, it acts like a mixed bag. It’s safe, fast, and time-efficient, which makes it convenient, but the high fares make it financially exclusionary for those who belong to economically marginalised classes. Hence, the concessional passes are not just for students but for all the people who live in Delhi and belong to low-income groups, which may help to mitigate their commuting challenges and make the metro more convenient for them.