🎧 Listen to the Article

This audio is AI-generated for accessibility.

Key Highlights

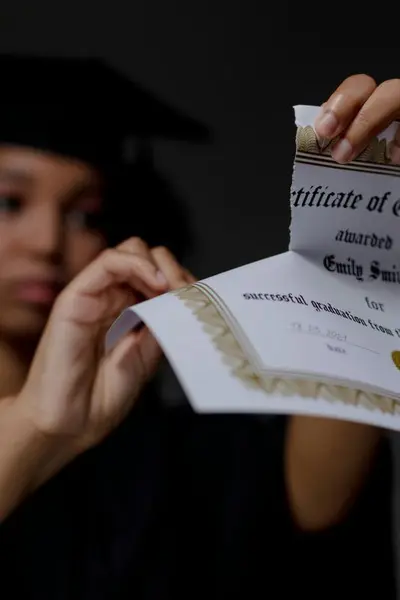

In India, where marriage is still seen as the ultimate measure of a woman’s success — often outweighing her education, career, and dreams — more women are now quietly challenging that collective psyche. Choosing peace, purpose, and self-respect over pressure for marriage, they are redefining singlehood from stigma to self-definition.

In India, marriage has long been seen as a woman’s greatest milestone of life, a symbol of respectability, stability, and family honour. This belief strongly prevails in poor and middle-class families across rural and suburban India.

For most women in India, marriage is often more than a personal choice. It often arrives as a deadline whispered by relatives, neighbours, demanded often by parents, sometimes by anyone who meets an unmarried woman. The message is clear: no matter how educated, independent, or capable she becomes, life is still considered ‘incomplete’ until she gets married.

But with time and changing mindsets, women across cities and small towns are starting to question this collective psyche towards marriage for women. A growing number are quietly redefining what it means to ‘settle down’ in life. Some are delaying marriage to focus on their careers amid unemployment, underemployment, job stress, or strong professional ambition; some carry heavy family responsibilities; while others are resisting it altogether, either after witnessing unhappy marriages around them or simply because they wish to live freely, without burdens. They are starting to decide for themselves if and when they want to get married.

Yet the pressure follows almost all of them like a shadow, disguised as love, advice, or concern. Financial or emotional independence brings a woman respect only up to a point. After that, it begins to invite suspicion, gossip, and pity, especially once she crosses 30.

For countless women, marriage remains more a compulsion than a choice. From parental influence to social scrutiny, from whispered pity and imposed shame to open pressure, the belief of ‘settling down’ follows women regardless of age, education, or career. Even in an era of gender equality, freedom and progress, an unmarried woman still carries the burden of explanation — as though independence needs permission, and singlehood is a flaw that must be corrected, through the institution called as ‘marriage’.

The core questions arise here: Can marriage in India truly be called a woman’s personal choice? Or is it a social compulsion disguised as tradition and love?

In a society that proudly calls itself modern and progressive, why does the freedom to marry or not to marry still come with invisible pressure, judgment, and emotional cost for women?

These are questions that demand honest reflection — not just from families or institutions, but from everyone who continues to measure a woman’s dignity by her marital status.

Tradition vs. Transition

From ancient times, Indian society has measured a woman’s worth through the lens of marriage and family. A daughter is often raised with care and affection, but also with an invisible expectation: one day, she must become ‘someone’s wife’. Her education, manners, and even dreams are subtly shaped to make her a ‘good match’. If she shows ambition, her career is quietly adjusted to fit that ‘match’. Marriage, in this view, is not a personal journey of a woman, but a family milestone — a proof that she has fulfilled her role.

This belief is centuries old in the country. In earlier times, marriage offered women what society denied them — financial security, social respect, and a sense of belonging. A woman’s identity was often shaped by the man she married and the home she maintained. That idea of complete womanhood through marriage still hums quietly in many Indian homes, especially in rural and semi-urban areas where change moves slowly.

Yet, a transition is coming. Education, economic exposure, and social awareness have begun to rewrite that old script. Many women no longer see marriage as the final destination but as one of many choices in a full life. They seek partnership, not dependence; respect, not permission. But tradition doesn’t vanish overnight. It hangs around in family conversations, neighbours’ remarks, and comparisons that remind women how far they have ‘deviated’ from the standard definition of ‘good women’. Between tradition and transition, they continue to walk a delicate line, carrying the hope of equality, yet weighed down by the memory of expectations.

Even today, Indian society, including many parents of daughters, remains hesitant to accept a girl who dreams beyond the ‘safe’ boundaries of a ‘teaching’ post or desk jobs with fewer work hours. Ambitions in fields like outdoor sports, defence, media, or outdoor pursuits such as photography, travel, riding, etc., are often seen as unsuitable for ‘marriageable girls’.

From the personal experience and observation by the author, this quiet restriction cuts countless wings before they even try to fly. When a daughter’s dreams and ambitions are filtered through her being a perfect ‘marriage material’, her potential, confidence, self-worth, and self-respect shrink unnoticed.

But women today are refusing to stay confined within the frame of a ‘good daughter’ or a ‘ideal woman’. They are rejecting the idea that silent suffering and obedience define good qualities. By choosing independence — in thought, work or lifestyle, they are quietly redrawing the lines of what it means to be a woman in India.

The Pressure to ‘Settle Down’

In almost every Indian family, the phrase ‘It’s time to settle down’ carries more emotional weight than it appears to. For men, it may mean finding stability in a career or life. But for women, it almost always means marriage. Once a daughter steps into her mid-twenties, even earlier in some communities, the unspoken countdown begins. Relatives grow curious, neighbours start asking, and even distant family members or people with no relation begin suggesting ‘suitable matches’.

This collective concern soon turns into pressure on the parents to make a ‘timely decision' and marry off their daughter. Her career, ambitions, and dreams slowly slide into the background, replaced by discussions about horoscopes and wedding dates. In the process, the woman herself becomes the ultimate silent sufferer, pushed to make the final ‘choice’ of marriage out of exhaustion and frustration.

The pressure of marriage usually does not come blatantly as a force. It comes in the form of affection, care, or concern — not for her dreams, education or career, but out of the family’s fear of social judgment: Why isn’t your daughter married yet?

Even against these odds, some strong and bold women take a stand for themselves and their choices in life. Their decision shocks almost everyone, because in many middle-class and poor households, people are still unfamiliar with women who speak up for their rights. As a result, such women often face judgment and isolation. Even parents begin to see them as a shame and burden or a strain on family prestige, no matter how independent or educated they are.

Their friends marry and drift away; invitations change from weddings to baby showers and children’s birthdays — sometimes to no invitation at all. Conversations shift to family life. Married friends, busy mothers, or women struggling in their own marriages often dismiss the opinions of their unmarried friends, implying that they cannot understand marital issues simply because they are not married. Even the most confident woman begins to question her worth for a moment and wonders if her independence has an expiry date.

The situation becomes even more complex when the woman is unemployed and financially dependent on her parents or others, even if temporarily.

For many, marriage becomes less about love and companionship, and more about social legitimacy, a mark that says she has finally done what she was supposed to. In this way, the idea of ‘settling down’ becomes anything but peaceful. It turns into a quiet performance of acceptance — a way to prove that she still belongs.

A Different Lens: The Northeastern Exception

While much of India still ties a woman’s worth to marriage, the picture is not uniform everywhere inside the country. In Northeast India, social and cultural values portray a more layered story that unfolds differently in many communities of the Northeastern states. Here, usually, social customs and community structures have long allowed women to live with dignity, with or without marriage.

In Meghalaya, for instance, the Khasis, Garos, and Jaintias follow a matrilineal system where lineage, family name, and inheritance pass through the mother’s side. Women are regarded as the natural heads of households after their mothers’ death. Children take their mother's surname. After marriage, men move into the wife’s family home, and the youngest daughter (called ka khadduh) is the custodian of the property. Unmarried women are treated with equal respect and dignity, free from any stigma or pity. Khasi women don't have to contend with the pressures of arranged marriages.

The article ‘Khasis: India's indigenous matrilineal society’ published on the BBC website in 2021 shows the balance that has shaped some of the most harmonious societies in the country — places with lower rates of marital conflict, dowry disputes, or domestic crime. Equality here is not a reform achieved through struggle, but a way of life quietly practised for generations.

These communities show that equality need not be borrowed from Western countries; it can grow naturally within our own traditions.

Assam, however, stands somewhere in between. Here, an unmarried woman is not openly condemned, yet her status remains uncertain — accepted by few, quietly questioned by the majority. Families may not force marriage outright, but concern and subtle emotional pressure persist, especially as women age. In urban spaces and cities, independence is admired; in smaller towns, it is tolerated with much hesitation. The result is an ‘average’ reality — neither hostile nor fully welcoming.

Together, these different experiences within Northeast India remind us that freedom is not just about laws or education — it is also about mindset. Where society trusts women to make their own choices, peace follows. Where it hesitates, invisible barriers remain.

Voices of Courage: Women Who Redefined ‘Settling Down’

Amid the constant social noise around marriage, some women quietly chose another path — either staying single by conviction, marrying late on their own terms, or stepping away from unhappy relationships with dignity. Their lives may not make headlines, but they redefine what it means to ‘settle down’, as explored in the India Today article ‘Will the surge in divorces and single living reshape Indian society?’ published in 2025.

To start with the Indian women celebrities, one of the most remarkable examples is Sushmita Sen — Miss Universe 1994, model, actress, and a proud single mother of two adopted daughters. She has often said in interviews that the reason she never married is simple: the men she met ultimately failed to meet her expectations. None, she explained, truly matched her values or lived up to what she expected from a partner, and her daughters were never the reason behind her singlehood, as mentioned in the Times of India article ‘When Sushmita Sen said she was on the verge of getting married with the wrong person: "I could have made a mistake”’ published in 2025.

Through her independence, confidence, and dignity, Sushmita has become an inspiration for countless young women who seek fulfilment beyond marital status. Yet, a glance at the online comment sections under such stories reveals something troubling — a flood of hatred, judgment, and character assassination. It shows that even one of India’s most accomplished women is not spared from social scrutiny because she remains unmarried.

Beyond public figures, many ordinary women quietly display extraordinary strength in choosing a different life path. Their stories rarely reach the spotlight, yet they speak louder than most speeches about women’s freedom and dignity.

One such woman, a private-sector employee from a middle-class family, grew up watching her mother endure years of domestic violence from her late father. That childhood pain left deep scars and shaped her disbelief in the social institution of marriage itself. Alongside, she also lives with certain permanent health conditions and hormonal imbalances that made her believe a married life could bring only suffering, both for herself and for any man she might marry. Refusing to let guilt or pity dictate her future, she chose singlehood with quiet conviction. “I’ve never been pressured,” she said calmly. “My mother and relatives respect my choice. I know marriage is not meant for everyone — and that’s okay.”

Another woman, a government school teacher now in her fifties, spoke to the author of a different kind of struggle. She always had relatives and parents with progressive liberal ideologies who, apart from useful, honest suggestions and concerns, never forced her to marry. They still casually suggest that she should have proper savings for old age. But the same could not be said of her surroundings. Colleagues at her workplace often humiliated her with invasive questions, asking if she was divorced, widowed, had kids, or secretly involved with someone. People rumoured about her character every time she met male friends with the same ideologies that led to hours of discussions on various issues of society, politics, life and the like. She had decided that marriage would make sense only if emotional maturity and shared values were present. She waited for such a person to appear, and when she finally met such a man in her late forties, she no longer felt the need to formalise it with a marriage certificate. Her family accepted her peace, but her workplace never did. “People couldn’t accept that a woman could live freely and still be respected,” she said, recalling the years of gossip and character assassinations she endured.

For me, the issue of marriage has never been distant or theoretical. Having grown up witnessing marital conflicts and emotional abuse in families around me, I developed an early distrust toward the idea of marriage itself. Despite holding a doctorate and dual master’s degrees, I have often been reminded, sometimes through subtle manipulation, sometimes through actions, that my singlehood overshadows every other achievement of my life and I am a strain on the family prestige. In the eyes of my parents, relatives, and close circle, I am seen less as a success and more as a question mark — someone who has failed to ‘settle down’.

The irony is sharp: career, ambition, education, and independence are applauded until a woman delays marriage. My refusal to compromise on the kind of life partner I truly want and deserve is often mistaken for arrogance. I have chosen to focus on my dream career rather than conforming to an expectation that would confine me. It is not society at large that judges me most; it is my own family’s quiet disappointment. That, perhaps, is the most painful form of pressure a woman can face.

From Pressure to Permission: A Quiet Shift in Families

Marriage in India has long been seen as an irreversible destination — once chosen, there was no return. For generations, wives had little choice but to compromise with their circumstances and surrender their sense of self. Bound by illiteracy, dependence, and the belief in fate, many accepted silence as survival.

There was a time when marriage was the ultimate commitment, and people looked down upon individuals who sought divorce for any reason, including domestic abuse, mental torture, or infidelity. Of course, the idea of a woman choosing not to marry was extremely offensive.

According to the Legal Crusader article ‘Divorce Rate in India: Trends, Causes, and Legal Insights [2025]’, the divorce rate in metropolitan cities has risen by 30–40% over the past decade. According to a 2023 study cited in the India Today article ‘Will the surge in divorces and single living reshape Indian society?’ published in 2025, conducted by the dating app Bumble, about 81% of Indian women prefer living a single life. But things are changing for the better.

As highlighted in the Legal Crusader article ‘Divorce Rate in India: Trends, Causes, and Legal Insights [2025]’, rising divorce rates are quietly breaking that long-held myth. Growing financial independence among women, changing ideas of dignity and self-worth, shifting gender roles, and emotional disconnection have made exits from unhappy marriages more visible and legally accessible, often for the good of both partners.

As a result, some parents who once believed that marriage was a permanent necessity are now beginning to reassess those assumptions. They are questioning whether pushing a daughter into wedlock is truly protective, or whether an unmarried, happy life may sometimes be the wiser, more peaceful choice.

This shift does not come easily. It grows slowly — through witnessing heartbreaks in other homes, through one’s own marital disappointments, and through the realisation that staying unhappy for the sake of society benefits no one. Many families are now learning that dignity lies not in ensuring a marriage happens, but in accepting a woman’s right to decide if it should happen at all.

Legal Rights of Unmarried Women: Empowering Choices and Fair Protections

For a long time in India, a woman’s social and legal identity was tied to her marital status, leaving unmarried women to stand outside the familiar frame of ‘respectable womanhood’. Laws once revolved around protecting her as a daughter, wife, mother or widow — not as an independent human being. Unmarried women often found themselves in grey areas of property rights, inheritance, and personal freedom.

Those who chose to stay unmarried or simply remained so by circumstance often faced quiet alienation and emotional exhaustion. The psychological toll on them has been deep and lasting. Their achievements are questioned, their choices doubted, and their independence mistaken for arrogance. It was against this backdrop of social struggle and silent hurt that India began to recognise the need for stronger, clearer laws that would protect a woman not because she is married, but because she is a person entitled to dignity, safety, and freedom.

Unmarried women face specific legal challenges and opportunities that are essential to navigate in today’s world. By delving into their rights, we can highlight the importance of empowerment and the various aspects of legal protections available. From property rights to family law, understanding these legalities not only ensures fair treatment but also fosters confidence and independence in their decision-making. Let’s explore the legal landscape that supports and protects unmarried women, paving the way for informed choices and greater equality.

Here are some of the key laws and provisions that protect and empower unmarried women:

These Articles guarantee equality before the law, prohibit discrimination against any citizen on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth or any of them, and deprivation of a citizen’s life or personal liberty. All of these directly apply to an unmarried woman as well.

While not designed specifically for unmarried women, this Act upholds the principle of free choice in marriage. It allows any adult woman to marry a person of her choice through a civil process, irrelevant of the religion or faith followed. In spirit, it reinforces the idea that marriage should be a matter of consent, not compulsion — a foundation that also validates a woman’s right to remain unmarried if she so chooses.

This landmark reform gave equal inheritance rights to daughters — married or unmarried, in their parents’ property. It ended centuries of discrimination and made daughters coparceners in ancestral property, with the same rights and liabilities as sons.

Though primarily used by married women, this law also protects unmarried women who experience violence or abuse within their own families or shared households. It recognises that emotional, physical, or economic abuse can occur beyond marriage — from fathers, brothers, relatives, or others in positions of control who live together in a shared household.

This Act entitles all mothers, including unmarried women, who become mothers, through natural process or adoption, to maternity leave and all related benefits in the organised sector, promoting respect and support for single motherhood.

Absolutely, irrespective of marital status, this law expands access to safe and legal abortion services on the therapeutic, eugenic, humanitarian and social grounds to ensure universal access to comprehensive care through safe and legal abortion up to 24 weeks of pregnancy, recognising their right to bodily autonomy and privacy.

This Act protects all women, irrespective of marital status, ensuring safe and respectful workplaces and establishing mechanisms for complaints and redressal. The Act applies to all workplaces, including government, private, and non-governmental organisations, as well as any organisation, institution, undertaking, or establishment.

Together, these laws and provisions of the Indian Constitution mark India’s gradual shift from viewing women through the lens of marriage to recognising them as independent human beings with equal rights and liabilities. Yet real change will come only when these protections are matched by acceptance and easy implementation in families, workplaces, and everyday life, so that no woman has to feel ‘different’ just for staying unmarried, for whatever reason.

The Way Forward

As the younger generation redefines relationships and self-worth, experts believe that the idea and philosophy of marriage in Indian society is quietly transforming, despite some rigidity still prevailing in the poor and lower middle class. The focus is shifting from social obligation to emotional well-being and mutual respect.

In the India Today article ‘Will the surge in divorces and single living reshape Indian society?’, published in 2025, Dr Nisha Khanna, a Delhi-based psychologist and marriage counsellor, says, “Millennials and Gen-Z prioritise personal well-being, career goals, and emotional wellness before committing to marriage. Marriage is now seen as just one aspect of life rather than a necessity. People are delaying marriage to focus on their careers, with many choosing to marry in their late 30s. Independence is valued more than ever, with fewer individuals willing to compromise for familial or societal expectations.”

The same article also cites Dr Chandni Tugnait, psychotherapist and founder-director of Gateway of Healing, who explains that for some, singlehood is a way of escaping rigid societal expectations. “It’s not about rejecting love or companionship,” she says, “but about rejecting the toxic structures that often come with them. It allows people to reclaim time, energy, and mental space without the pressures of traditional roles.”

In the BBC article ‘The Indian women calling themselves ‘proudly single’, published in 2022, it was reported that according to the 2011 Census, India is home to 71.4 million single women. Writer and activist Sreemoyee Piu Kundu, founder of the Facebook community Status Single, urges women to embrace their identity with pride: “Let’s stop describing ourselves as widows, divorcees, or unmarried. Let’s just call ourselves proudly single.” The community brings together teachers, doctors, lawyers, professionals, entrepreneurs, activists, writers, and journalists — some separated or widowed, others never married.

The article above also highlights how even marketers are beginning to acknowledge the growing independence of urban single women. Wealthy, self-reliant women are increasingly recognised as an emerging economic segment — courted by banks, jewellery brands, consumer goods companies, and travel agencies. Single women are also finding space in popular culture, with Bollywood films like Queen and Piku, and web series such as Four More Shots Please! featuring single female protagonists and performing commercially well. Yet, despite these welcome shifts, social attitudes remain rigid. As Ms. Kundu observes, being single is not easy even for the affluent — they continue to face constant judgment and scrutiny.

Looking at the changing pattern of social attitudes toward marriage — from viewing it as a woman’s ultimate milestone in life, to granting hesitant permission to remain unmarried, and now to very slowly accepting singlehood as normal — Indian society appears to be moving toward eventual neutrality, where a woman’s marital status is simply irrelevant.

Although the transition is very slow, the growing self-awareness of women in their pursuit of happiness, dignity, and self-fulfilment will gradually shape a more balanced and compassionate society in India. In the future, ‘marriage’ for women in India is expected to truly become a matter of personal choice, not compulsion. Law will keep pace — but the real change will be cultural: a quiet understanding that partnership is one option among many, and that an unmarried woman’s life needs no explanation, apology, or defence.

Conclusion

The paradox of marriage for Indian women is ultimately not about choosing between tradition and rebellion. It is about reclaiming ownership of one’s life. As the illusion of ‘social approval’ slowly fades, more women are realising that self-respect, dignity, and peace matter more than compliance and chaos. The next phase of India’s progress will not be measured by how early women marry, but by how freely and happily they live. When singlehood is seen not as defiance but as dignity, society will have finally matured — not just for women, but for everyone.