🎧 Listen to the Article

This audio is AI-generated for accessibility.

Key Highlights

Educated unemployment in India—especially among postgraduates and PhD holders—has quietly become both a mental-health and economic crisis. When years of study end in uncertainty, confidence fades, productivity suffers, and the nation loses its brightest minds to frustration and despair. The need is not only for jobs, but for empathy, structured mental-health support, and institutional reform—where universities, families, and policymakers work together to rebuild dignity, direction, and purpose for India’s educated youth.

“So, you’re a Doctorate? Where are you working now?”

It’s often the first question people ask a highly educated youth, and the one that cuts the deepest when the honest answer, “nowhere,” can’t be spoken aloud. Instead, come soft replies like “still applying” or “waiting for interview results,” disguised behind polite smiles. Behind those forced smiles lie layers of anxiety, frustration, and quiet shame. After years of education and glittering degrees, many find themselves unemployed, financially dependent on their parents, and battling an invisible burnout that society refuses to acknowledge.

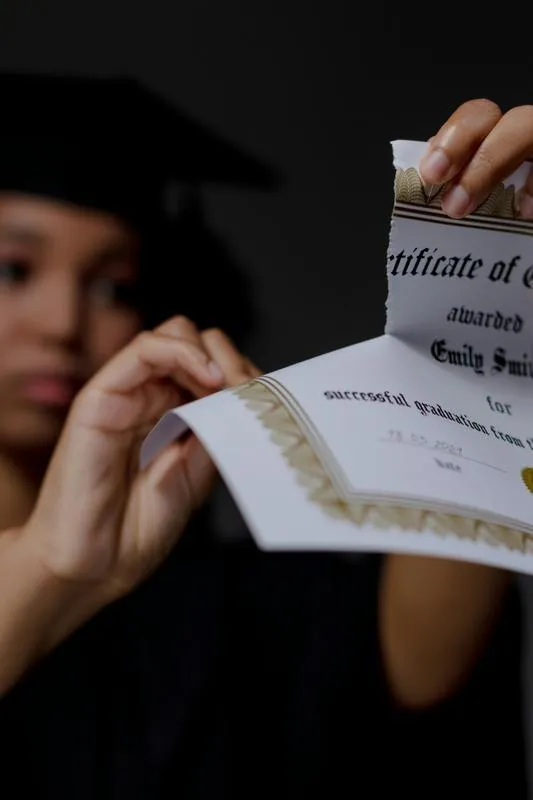

For lakhs of young Indians, unemployment is not just about the lack of a job; it is the erosion of identity. Behind glowing academic certificates and years of hard work lies a harsh reality: degrees no longer guarantee employment, and unemployment quietly steals away one’s dignity. The long-held promise that education leads to stability now feels broken, leaving many post-graduates and PhD holders trapped between over-qualification and underemployment. While policymakers discuss statistics and job schemes, the psychological and human cost remains invisible — sleepless nights, fading confidence, growing depression, and the same silent question echoing in every middle-class home: “Was all this education worth it?”

When Higher Education Meets a Shrinking Job Market

According to the All India Survey on Higher Education (AISHE) 2021–22, conducted by the Ministry of Education, Government of India, India had 2.13 lakh PhD students enrolled, with 32,588 doctorates awarded during that year. At the post-graduate level, 14.8 lakh students completed their degrees.

According to the article ‘Joblessness is far worse than we thought it was’ published by The New Indian Express in 2025, India’s unemployment crisis continues to deepen. The government’s Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) reported that unemployment rose to 5.6% in June 2025, up from 5.1% in May 2025. Meanwhile, independent estimates from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) place the unemployment rate even higher, at 7.0% — highlighting the severity of the gap between qualifications and available opportunities.

Behind these figures lies a growing contradiction: while India continues to produce highly qualified graduates in record numbers, meaningful employment opportunities have not kept pace. Each year, thousands of post-graduates and doctoral students enter a job market that seems too narrow for their qualifications. It is a mismatch that quietly fuels disillusionment, financial dependence, and mental exhaustion across the country. And above all, Artificial Intelligence is now replacing many entry-level roles, and the few opportunities that once existed are shrinking further for educated job seekers in certain sectors. While unemployment troubles graduates across India, it weighs heaviest on those who went further — post-graduates and PhD holders who find themselves overqualified, underemployed, and emotionally drained.

The painful irony is that many of these students are extremely capable, sharp thinkers, high scorers, problem-solvers — but they are trapped in a system where academic brilliance does not guarantee a livelihood, let alone the life they dreamed of. India's traditional marksheet-focused education model is slowly shifting toward skill-based, application-driven learning, but this transformation has not reached every institution or every corner of the country.

As a result, a generation of bright, ambitious young people now finds itself labelled as ‘misfit’ — not because they lack talent or clarity, but because the degrees they earned with dedication do not align with the demands of a rapidly changing world. It is not that the students lack direction - it is the system that failed to evolve in time, leaving them stranded between knowledge and employability, aspiration and opportunity.

The Psychological Toll of Joblessness

Anxiety, Shame, and Silent Burnout

Unemployment is not just an economic statistic. It is a lived reality that shapes how educated youth see themselves. For many post-graduates and PhD holders, the absence of earning gradually erodes confidence and identity. Each job rejection feels like a personal failure; even casual family conversations start carrying an invisible discomfort.

In middle-class families, where education is treated as both aspiration and investment, joblessness becomes a source of quiet shame. The parents who once introduced their child proudly as “doing a PhD” now avoid the subject altogether. The same degrees that once symbolised pride begin to feel like a burden, now reminders of expectations unmet.

Psychologists describe this growing exhaustion as silent burnout — not from overwork, but from endless effort without results. It manifests as a loss of motivation, disturbed sleep, and a decline in interest in personal goals. Over time, even success in smaller tasks feels hollow.

The digital age amplifies the pressure. Colourful social media timelines of others filled with job updates, promotions, foreign trips, or ‘big announcements’ become daily reminders of comparison. To cope, many unemployed youth retreat into selective isolation: posting old pictures, offering polite excuses, and cutting social contact to avoid judgment.

According to the United States National Library of Medicine, in its research article titled ‘Unemployment and Mental Health: A Global Study of Unemployment’s Influence on Diverse Mental Disorders’, unemployment significantly heightens the risk of mental illness worldwide. The study states: “Globally, one in five individuals faces unemployment, which substantially increases their risk of developing mental disorders. The analysis reveals a significant positive association between unemployment and mental disorders, particularly anxiety, depression, and bipolar disorder. Moreover, distinct patterns emerge, linking unemployment to higher rates of drug use and eating disorders in specific demographics. The consequences of unemployment, such as financial strain and social pressures, often lead to severe stress and depression. Unfortunately, this situation worsens within a society that lacks robust support systems. Ultimately, unemployment detrimentally affects various aspects of mental health.” The study covered 201 countries.

From Degrees to Skills: The Transition India Wasn’t Ready For

For decades, India’s education system was designed around marksheets, merit lists, and formal degrees. Success was disguised as high scores and great certificates, not necessarily developing practical skills essential for growth in the modern world. As the job market evolved, employers began valuing communication, adaptability, digital literacy, and real-world problem-solving over exam scores.

The country’s slow pivot from degree-based validation to skill-based employability, however, has left an entire generation caught in between. Many Millennials and young post-graduates are in this transition phase — educated in theory but unprepared for practice, now facing the harsh reality of being under-skilled for modern employment despite being overqualified on paper. This has quietly created a generation of disillusioned youth, struggling to bridge that distance through unpaid internships or costly upskilling courses.

By the time the focus shifted toward ‘skills’, they had already completed their education, stepping out into a world that judged them for not being industry-ready. For these youth, the result is a double crisis — academic exhaustion from years of competitive learning, followed by emotional frustration when that learning no longer translates into livelihood. Employers expect them to ‘upskill’, but most cannot afford expensive courses or unpaid internships. Many even feel betrayed by a system that promised opportunity through education, only to change the rules midway.

This slow mismatch between academia and employability has quietly widened India’s skill gap. While policies like ‘Skill India’ and ‘Digital India’ aim to bridge the divide, for many highly educated yet jobless Indians, the transition came too late — leaving them caught between two worlds: degrees that no longer guarantee work, and skills they were never taught to build.

Behind the Degrees, Behind the Pain

According to the article "Broken Dreams: The Story of India’s Unemployed Youth" published in Congress Sandesh (INC media platform), Brijesh Pal, a 28-year-old youth from Uttar Pradesh, died by suicide in February 2024 after the Uttar Pradesh police recruitment exam was cancelled due to a paper leak, which shattered his last hope for employment. Before taking his life, he left behind a heartbreaking note to his parents — a note full of guilt, helplessness, and despair. “Today is the last day for me. Today I had dinner with my mother, and I am going to cheat my parents. Taking care of Papa and telling him, I was with you only this much. ……... I have burnt all my B.Sc papers. What is the use of a degree that cannot get me a job? Half of my life has been spent studying, hence my heart is filled.’’

(Note: If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, please reach out to a mental-health helpline or trusted person immediately. Help is available.)

The Uttar Pradesh police exam he pinned his future on had 50 lakh applicants for just 60,000 posts. When the paper leak crushed the recruitment, so did the futures of lakhs of aspirants like him.

In the same state, thousands of educated youths have applied for labour-class jobs in Israel — in a war zone, believing that dying in a foreign land may feel less painful than dying unemployed at home.

This is not just a news incident.

The tragedy of Brijesh is not an isolated incident. It is a mirror held up to a nation where degrees often fail to convert into dignity. And across India, many such lives sit at the edge of frustration, uncertainty, and grief. Some speak, some suffer quietly, and a few revolt against silence itself.

Young Indians are living this struggle every day. A powerful Article 14 feature titled ‘Survival Is Hard’: India’s Millions of Unemployed Youth & the National Crisis Facing Modi 3.0 captures just a few of these lives, each marked by ambition, frustration, and resilience.

Take Neelam Azad, a postgraduate from Haryana who taught UPSC aspirants, ran a small library at home, and even worked as an MNREGA labourer for ₹380 a day when no dignified job came her way. When she protested inside Parliament in December 2023 to draw attention to unemployment and farmers' distress, she was arrested under UAPA and spent months in Tihar jail without bail. In a nation where educated youth are losing hope, Neelam’s story shows how even demanding dignity can come at a price.

Then there is Ajay Chahal, a postgraduate in Public Administration, who cleared multiple stages of police and defence recruitment exams — CRPF, state police, even the army, only to be defeated by shifting rules, like the Agnipath scheme. Year after year, the goalpost moved, opportunities disappeared, and the promise of government employment faded, leaving him stuck between qualification and a shrinking future.

And Mehul Kumar from Ahmedabad, a PhD in Sociology who cleared UGC-NET, applied to nearly 500 academic and social-sector jobs, only to be rejected again and again — often labelled 'overqualified'. The weight of rejection pushed him into therapy during the pandemic, as hope and confidence thinned under the burden of merit without opportunity.

These are not isolated stories. They reflect a national crisis. For every Neelam, Ajay, or Mehul, there are thousands of young Indians sitting quietly at home, clutching degrees that once promised dignity and opportunity, now battling financial stress, self-doubt, and shrinking hope. They did everything society asked of them. They studied hard, earned qualifications, believed in merit, only to discover that the system had no room for them.

These stories reflect a painful irony — in a country that celebrates education, brilliance can become a burden when the job market has no space for it.

A Crisis Larger Than Individual Stories

In 2018, the article ‘Over 93,000 candidates, including 3,700 PhD holders apply for peon job in UP’ published in The Economic Times revealed a shocking picture: more than 93,000 applicants, including 3,700 PhD holders, 50,000 graduates, and 28,000 post-graduates, applied for peon posts that required only a Class 5 pass and the ability to ride a bicycle. The job offered a starting salary of around ₹20,000 per month — an amount that tragically remains beyond the reach of many highly educated young Indians even today, after paying the bills.

Around the same time, over 2 crore applicants applied for just 1 lakh vacancies in Indian Railways. In contrast, 2 lakh candidates, including engineers, doctors, and lawyers, competed for 1,100 constable posts in the Mumbai Police. In Rajasthan as well, 129 engineers, 23 lawyers, 1 CA, and 393 post-graduates turned up to interview for peon jobs.

These numbers don’t just reflect desperation. They expose a disturbing reality: India is producing highly qualified youth faster than it is creating dignified employment, pushing brilliant minds toward jobs far below their potential. It is a terrifying portrait of a generation pushed to its breaking point — not by failure, but by a system that failed them.

Besides, for many unemployed post-graduate and doctorate youths in India, the deepest pain is applying for the lowest-grade jobs, not because any job is small, but because their dreams and hopes feel crushed after years of study and sacrifice, when they helplessly apply for those jobs.

What Educated Unemployed Youth Told Us

To understand the emotional undercurrent behind educated unemployment, the author reached out directly to unemployed post-graduates and PhDs through a personal Google Form. The responses reveal a quiet, heavy truth.

Most participants shared that family and social reactions to their unemployment are discouraging, often marked by subtle judgment. As one post-graduate respondent put it: “Family supports my situation, but society’s hypocritical soul does not.” Women pursuing PhDs noted that while their families currently encourage them to focus more on research, financial stress still weighs on them; many hesitate to burden their middle-class parents any further, after years of costly education.

Only one respondent — a PhD seeking an Assistant Professor position reported feeling genuinely supported and unpressured by parents. Her family’s understanding of the harsh job market and respect for her individuality stand out as a rare exception.

A considerable portion admitted feeling over-qualified for the jobs available in the real-world job market. One respondent summed up the frustration sharply: “Our academic documents are only pieces of paper, with outdated syllabuses.”

Some have explored freelancing or upskilling, hoping to unlock new opportunities. One post-graduate shared that he has already pursued law and is “trying to focus on new areas like cyber law, but government organisations are under-prepared.”

However, many resist switching fields — not out of rigidity, but because the other options would take more time to acquire and master the ‘skills’ as well, and they need to start as a fresher after years of academic investment.

The emotional battle inside oneself is real. Respondents spoke of slipping confidence, anxiety, financial strain, and battles with self-worth, especially when asking parents for money post-degree. Yet, resilience persists. As one respondent beautifully expressed, “Every human has their own different journey from birth till death. Spiritualism helps me a lot.”

They hold on to self-belief and try to keep themselves motivated. They also accept the reality that in a country this big, getting the job you truly deserve doesn’t come easily.

Strikingly, every participant agreed on one thing: educated job-seekers in India do not receive adequate emotional or professional support. Behind polite smiles and academic titles, India’s unemployed scholars are silently carrying the weight of expectation, uncertainty, and hope.

What Mental-Health Experts Are Seeing

To understand the psychological impact of educated unemployment beyond statistics and news reports, I spoke with Dr Jyotirmoy Das, one of the leading senior psychiatrists in Northeast India.

He explained that unemployed post-graduates and doctoral scholars face a unique burden: exceptionally high expectations from family and themselves, and a job market unable to absorb them.

“The post-graduates or PhD scholars do not belong to the normal ‘unemployed’ group of the population. In India, the higher you study, the deeper the disappointment hits when you don’t find a suitable career. More expectations create more frustration, leading to anxiety, self-doubt, and silent burnout.” Dr Das noted.

After years of intense study and sacrifice, even considering low-paid or unrelated work feels emotionally devastating. “They don’t want to take a sub-standard job. But sometimes they apply for Grade-IV posts not out of choice — but because they have no option left.”

Dr Das highlighted that family dynamics often intensify their struggle.

Even loving families can unintentionally intensify distress through subtle pressure, comparisons, or silence. This pressure is heavier in economically weaker households where survival needs override emotional support.

“Strong emotional support is possible mostly in financially stable families,” he explained.

“In struggling households, patience runs out. This is India. Here expectations rise faster than opportunities. Parents wait for some time. Then fear sets in. They start losing hope and pressure their children to do ‘something practical’. Not every family can support long years of unemployment; they are fighting their own battles.”

This, he says, pushes many into self-doubt and psychological distress.

“When your family sees even highly-educated people failing around you and them, it shakes everyone’s confidence.”

With no income, many highly educated unemployed youth cannot afford professional therapy, even when they desperately need it.

Dr Das suggests realistic coping tools:

- Using Government toll-free mental health help lines like Tele MANAS for India

- Sharing emotions and problems with trustworthy, non-judgmental peers

- Build small support circles with fellow job-seekers with almost the same qualifications

He advised: “Expressing frustration in a safe space brings relief, even without immediate solutions. Their struggles are similar — they can support each other instead of suffering alone.”

And above all, he reminds young job-seekers to hold on to hope and patience.

“They should tell themselves and their families that the pay may start small, but with dedication, it can grow. Opportunities do come. But until then, emotional support is essential.”

Breaking the Stigma: The Need for Emotional Support

In many Indian households, unemployment after earning a post-graduate or doctorate is discussed but not in terms of guidance or care. Instead, it comes with subtle taunts, comparing or humiliating the youth, despite their high qualifications and proven academic excellence. Both men and women face this emotional burden though the dynamics differ. Some women share that while their families allow time for research, they still struggle quietly with finances and fear of being seen as ‘dependent’. Men often report feeling the need to prove themselves, and when no job appears, the sense of no respect and failure hits hard.

For many educated job-seekers, the hardest part is not the job market, it is the fear of being misunderstood at home. Instead of emotional support, they often face comparison, doubt, or unsolicited advice. Even in some loving families, quiet disappointment hangs in the background. Society adds another layer. Neighbours, relatives, and acquaintances rarely ask how an unemployed youth is coping — they only ask what they are doing now. So many young people withdraw, speak less, avoid social gatherings, and pretend to be ‘busy’ to protect their dignity. This stigma creates loneliness. People battling unemployment often suffer in silence because they don’t want to be judged as lazy, unambitious, or incapable. They are not asking for sympathy; they are asking for understanding, patience, and emotional space to deal with one of the toughest phases of their life.

According to the article ‘2020 stats: 30 suicides/day due to poverty, unemployment’ (The Times of India, 2021), over 10,600 people in India died by suicide in 2020 due to unemployment, poverty, or debt — an 8% rise from the previous year. Official NCRB data shows that at least one person, on average, took their own life every hour because of joblessness or financial stress. Suicides linked specifically to unemployment rose sharply, nearly a quarter higher than the previous year. Mental-health experts cited in the report say many of those struggling never reach professional help, not only because of stigma, but because therapy itself feels unaffordable when someone has no income. Behind these numbers are real stories of educated and hardworking individuals whose dreams collapsed under economic pressure and emotional isolation. The painful truth is this: many of these lives might have been saved had they simply been given the dignity of secure employment.

Some youths are already quietly seeking free therapy, counselling sessions, and even online support groups. Some others are slipping into darker coping mechanisms — from isolation to substance abuse, drowning quietly under pressure. Others remain silent, trapped under the weight of expectation, rejection and self-doubt. They say what they need is not another job advertisement, it is empathy, emotional support and the freedom to try again without shame.

We must finally see this truth: jobs don’t just build livelihoods, they build lives, dignity, and hope. So, when the system fails, strong emotional support becomes essential. Families, educational institutions and workplaces must step in with more than advice. They must step in with understanding, space, inspiring practical suggestions, and professional mental-health support. For the educated unemployed, especially those beyond graduation, this may be what truly helps them rebuild themselves, not just build a dry resume.

Institutional Responsibilities: Supporting the Educated but Unemployed

Families can and should offer empathy to their unemployed post-graduate and PhD-holder youths, but at this stage, the role of educational institutions becomes crucial.

For India’s growing population of educated yet jobless youth, universities and colleges cannot end their responsibility by merely handing out degrees and bidding farewell on Convocation Day. These institutions shape not only intellectual excellence but also the emotional resilience of those stepping into a job market that offers very limited opportunities for absorption.

Colleges and universities must go beyond revising curricula from theory-based learning to skill-oriented education. They should also be mandated to provide long-term, affordable career counselling, psychological support without judgment, and alumni mentorship until students find stable ground. Institutions must hold themselves accountable for preparing their graduates not only for employment, but also for the emotional realities of delayed or uncertain employment.

Most Indian universities still lack career support cells or mental-health outreach programmes dedicated to post-graduates and research scholars — the systems that could prevent many from slipping from disappointment into despair.

Ultimately, education must evolve beyond producing scholars on paper to nurturing emotionally resilient, employable citizens who can transform knowledge into meaningful lives.

Closing Reflection

Educated unemployment in India is not just about a lack of jobs against a huge number of post-graduates and Doctorates. It is about the silent emotional strain carried by those who expect a dignified life and real opportunities after years of hard work, hope and dreams. Instead, many face frustration, depression, self-doubt, social pressure, withdrawal and isolation, while quietly forcing themselves to stay motivated in a system that changed faster than they could as they were packed inside the conventional system. What they need most today is not judgment or comparison, but understanding, patience, and emotional support until real opportunities arrive. When society recognises that jobs build confidence and identity, not just income, it will finally be able to support the very talent it depends on for progress.