🎧 Listen to the Article

This audio is AI-generated for accessibility.

Key Highlights

Assam’s fight for the protection of its socio-cultural and linguistic identity continues — this article explores the journey from the Assam Movement (1979–1985) to the anti-C(A)A Movement 2019, and why the protests refuse to be forgotten.

Guwahati, November 2019 — the gateway to the entire Northeast, was eerily still. National Highway 17 — the region’s vital road link to the rest of India- lay deserted under curfew. The highway, normally alive with the constant roar of vehicles, including heavy loaded night trucks, stood silent. The only sound breaking the emptiness was the rumble of paramilitary trucks carrying ‘jawaans’ to ‘control the situation’. A few young residents stood on the empty road, their hearts heavy with anxiety, frustration, and helplessness.

Protest rallies against the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill (C(A)B) had already erupted across Assam, with Guwahati as the epicenter. Lakhs of people thronged the streets against the C(A)B — and later the Act — shouting “Jai Aai Asom” (Hail, Mother Assam!). Representatives from non-Assamese and Muslim communities joined the marches alongside native Assamese protesters, creating a rare moment of solidarity (Times of India, 2019).

In an attempt to stop the movement from spilling onto the streets again, the Government imposed a strict curfew — yet the anger only grew louder. The Asam Sahitya Sabha- Assam’s premier literary body, staged a sit-in followed by a mass procession demanding the Bill’s withdrawal. Even government employees under the Sadou Asam Karmachari Parishad (SAKP) and the Assam Secretariat Service Association (ASSA) joined in, observing a complete cease-work day.

[ Image source: Dasarath Deka, Senior Photojournalist (used with permission) ]

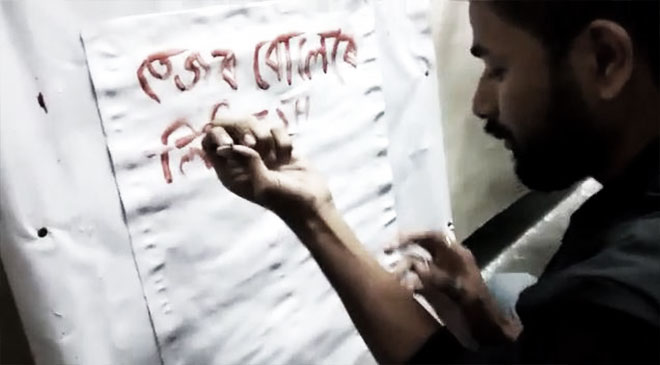

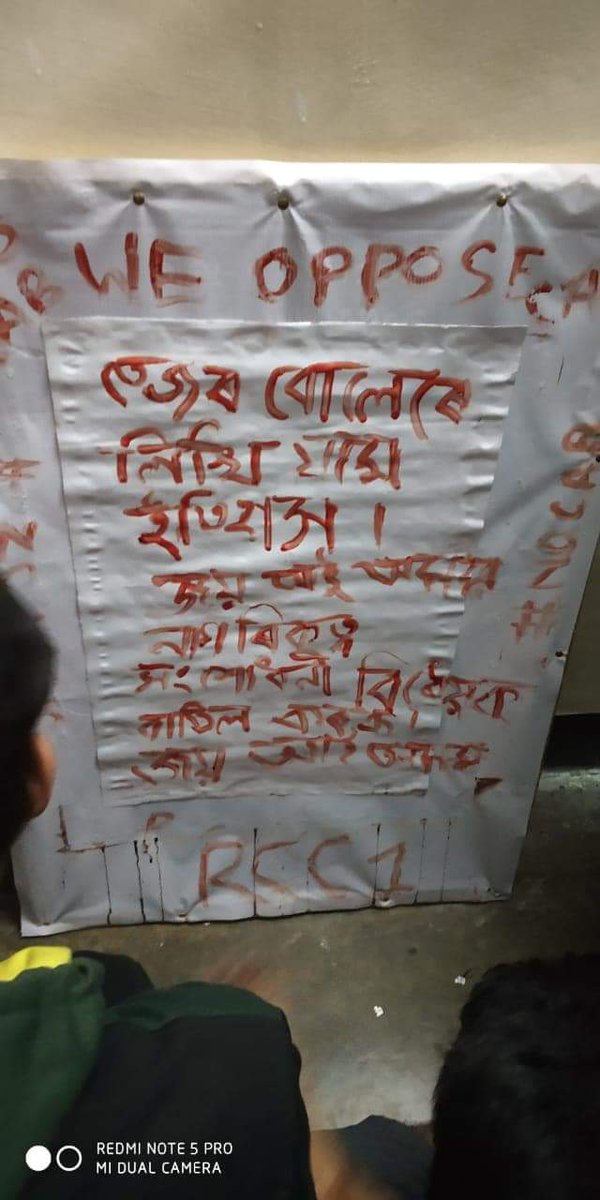

In one of the most striking scenes, Gauhati University students slit their wrists and wrote anti-C(A)A slogans with their own blood — a moment widely reported at the time; students from Cotton University and almost all other campuses joined in Guwahati (NorthEast Now, 2019), (India Today NE, 2019).

[ Image Source: NorthEast Now (used with permission) ]

[ Image Source: Neeva Dutta (X- formerly Twitter) ]

Assam police deployed tear gas and imposed curfew in many areas of the state. The government cut off internet services for ten days, and public transport was curtailed. Both the Central and Assam governments pressed ahead with the then Bill, showing little concern for public opinion or anguish. The protests were brushed aside, and the Citizenship (Amendment) Act (C(A)A), 2019, was pushed through. Five young boys were shot dead — martyrs of this movement — while many more were injured, beaten, or arrested alongside political and civic leaders.

But the anti-C(A)A protests of 2019 were not the end of the struggle to protect the Assam Accord and the Assamese identity through its Clause 6. They continue to echo in today’s Assam, especially after the Central Government’s recent decision to extend the cut-off date for C(A)A to December 31, 2024 — a move that has reignited debates over identity and justice. This context makes the following analysis relevant today.

Citizenship (Amendment) Bill and Act 2019

The Citizenship Act of 1955 lays down the rules for acquiring Indian citizenship. Under the Foreigners Act, 1946, and the Passport (Entry into India) Act, 1920, illegal migrants are liable to imprisonment or deportation, as these laws empower the Central Government to regulate the entry, stay, and exit of foreigners.

In 2015 and 2016, the Government issued notifications exempting illegal migrants belonging to Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi, and Christian communities from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan who had entered India on or before December 31, 2014, from provisions of the Passport (Entry into India) Act, 1920, and the Foreigners Act, 1946. Effectively, they could no longer be deported or imprisoned for lacking valid documents. The exemption excluded the tribal areas of Assam, Meghalaya, Mizoram, and Tripura covered by the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution, as well as the states under the Inner Line Permit system (Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram, and Nagaland).

Building on these notifications, the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, 2019, was introduced in the Lok Sabha by Home Minister Amit Shah on December 9, 2019. It was passed the next day, cleared the Rajya Sabha on December 11 (Press Information Bureau, Government of India), and received presidential assent on December 12, 2019. The Act was subsequently notified in the Gazette of India and brought into force from January 10, 2020, through Notification S.O. 172(E) of the Ministry of Home Affairs.

The Act that Breached the Trust of Assam

Protesters in Assam and other northeastern states do not want Indian citizenship to be granted to any refugee or immigrant, regardless of their religion, as they fear it would alter the region's demographic balance, resulting in a loss of their political rights, culture, and land. They are also concerned that it will motivate further migration from Bangladesh, which could violate the Assam Accord. "The bill will take away our rights, language, and culture with millions of Bangladeshis getting citizenship," Gitimoni Dutta, a college student, said at a protest in Guwahati. People in Assam and surrounding states fear that arriving settlers could increase competition for land and upset the region's demographic balance. Some opposition Muslim politicians have also argued that the bill targets their community, which numbers more than 170 million people and is by far India's largest minority group. (Reuters, 2019)

The C(A)A, 2019 is widely known. Yet very few from mainland India understood, in fact, cared enough to understand the particularly damaging effect this Act would have on Assam’s demographic and socio-cultural balance. To grasp why Assamese people protested C(A)A 2019 with such intensity, one must revisit the history of illegal immigration, the Assam Movement, and the Assam Accord. However, this does not imply support for violence by both parties – the protesters and the Government Security forces.

The Detection of Illegal Immigration: Flashbacks

The issue of illegal immigration in Assam was first detected in 1979 in the Mangaldoi constituency. A by-election held after the death of a sitting MP revealed that nearly 72% of ‘Doubtful Voters’ were confirmed as non-citizens. This shocking discovery spread quickly: if one constituency showed such numbers, what was the scale across the entire state?

Thus began the All Assam Students’ Union (AASU) and All Assam Gana Sangram Parishad (AAGSP)-led Assam Agitation (1979–1985), demanding the detection, deletion, and deportation of illegal immigrants. Over six years, 855 lives (later on 860 as submitted by AASU) were lost in the protests, many killed by security forces. Khargeswar Talukdar, the first martyr, was beaten to death. They are remembered as martyrs, not victims.

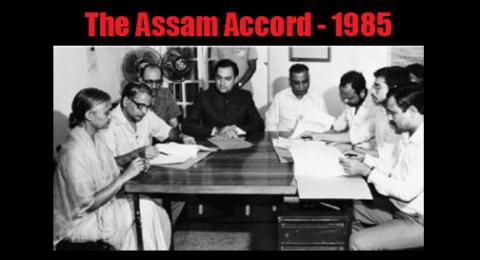

[ Image Source: Government of Assam — Implementation of Assam Accord (Official Photo Gallery) ]

The movement ended in 1985 with the signing of the Assam Accord between the Centre and Assam Movement leaders, in the presence of Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi. The Accord promised detection, deletion, and deportation of illegal immigrants, with March 25, 1971, as the cut-off date for citizenship. Yet decades later, none of these promises were kept.

[ Image Source: Government of Assam — Implementation of Assam Accord (Official Photo Gallery) ]

The C(A)B 2019, however, directly contradicted this promise. By allowing persecuted minorities from Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Bangladesh to gain citizenship if they entered India by December 31, 2014, it undermined the Accord’s cut-off date of March 25, 1971. C(A)B’s exclusion of Muslims also violated India’s Constitution. The amended Preamble of the Indian Constitution of India says, "We, the People of India…" and declares India a Sovereign, Socialist, Secular, Democratic Republic. Besides ignoring the element of ‘Secular’, the ruling party has directly clashed with Article 14 of the Indian Constitution that says “The State shall not deny to any person equality before the law or the equal protection of the laws within the territory of India”, and excluded Muslims from citizenship — a vote-bank strategy.

The Clash between Assam Accord, NRC & C(A)A 2019

Elsewhere in India, the Foreigners Act, 1946, applies with a cut-off year of 1951, whereas in Assam, the Assam Accord fixed 1971 as the year of reference. The National Register of Citizens (NRC) was intended to identify legitimate citizens and remove undocumented immigrants. But the exercise remains incomplete, leaving the core issue unresolved. The NRC published in Assam on August 31, 2019, left over 19 lakh people excluded, many women and rural poor lacking pre-1971 documents. They must appeal to a Foreigners’ Tribunal. The process was criticised as unclear, error-ridden, and socially disruptive. Critics argue that rather than fulfilling the Assam Accord’s spirit of protecting Assamese culture and rights through Clause 6, the NRC deepened divisions and mistrust, exposing both the fragility of documentation and the failure of governance to settle a decades-old issue. And this is the year when the Government introduced C(A)A 2019—the Act that excluded Muslims from applying for citizenship. Now the question is- what will happen to the thousands of genuine Muslim people whose names did not come in the NRC of 2019, which was the result of a system failure!

Silent Hands Stained in Blood

Both the Centre and State, and certain opportunist public figures, stood silent as armed forces assaulted unarmed protesters. Though the anti-C(A)A movement in Assam began as a raw, student-led uprising, parties and public figures entered, diluting the movement’s burning spirit and giving the Government a chance to extinguish it. They washed their hands with the blood of five martyrs — Sam Stafford, Dipanjal Das, Ishwar Nayak, Abdul Alim, and Dwijendra Panging. Regional newspapers called Das the ‘first martyr’ (shaheed) of the anti-C(A)A movement. Writers were arrested for poems shared on social media. Protest supporters were branded traitors. In Assam today, dissent itself risks criminalisation.

[ Image Source: Pratidin Time – “The Fight is Not Over: Assam Pays Tribute to Five CAA Protest Martyrs” (Published Dec 12, 2024) ]

Further Extension of the Cut-Off Date: A Quieter Assam?

In a recent move, the Ministry of Home Affairs extended the cut-off date for citizenship applications under the C(A)A to December 31, 2024, through the Immigration and Foreigners (Exemption) Order, 2025. This decision allows entry, stay, and exit of people from six minority communities of Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan who entered India without valid documents until the new cut-off date.

For many in Assam, this felt like the final and extreme breach of trust regarding the Assam Accord — now with the Centre’s backing and the State Government’s support. Yet, surprisingly, this time the protests have been relatively subdued. Assam Jatiya Parishad, All Assam Students’ Union (AASU), and Assam Sammilita Morcha have staged demonstrations, but the overall scale of protest has not matched that of 2019.

To understand this shift, the author reached out to prominent voices. Utpal Bora, Deputy Editor of The Crosscurrent, an independent media house in Assam, shared in a written statement to this writer:

“The number one reason why the Assamese nation did not launch the anti-C(A)A movement again is the compromise of the national parties and organisations. Most have zero spirit of sacrifice anymore. Some have abandoned the character of nationalism and now adopted the character of Hindutva. Secondly, there is a lack of public confidence in the organisations that provide leadership. The overall lack of results of movements since the Assam Movement has made the people disillusioned. Thirdly, there is a lack of awareness among the people. They have failed to realise the seriousness of this law, and the rulers have divided and confused them in various ways.”

On the near-absence of student-led agitation compared to 2019, he added:

“There is a lack of leadership in the student community now. It was also disappointing that some adopted an opportunistic character after the 2019 anti-C(A)A movement and joined the ruling party. Meanwhile, the current education and social system has made students more disengaged. The semester system has even killed the excellence of students.”

Speaking to this writer, Ravi Sarma, an acclaimed Assamese film and theatre actor plus social activist, known for his uncompromising ideological stand and outspoken opposition to C(A)A 2019, offered a perspective that speaks to Assam’s caution today:

“We lost five young boys in the violent clashes of 2019. This time, nobody is willing to take that accountability. Responsible civilians are choosing non-violence. Based on what we saw last time, we know that the moment citizens return to the streets in direct conflict, political forces in power will use that opportunity to destroy public and private property themselves — just to shift the blame to protesters, like before. We all witnessed how they used diversionary tactics last time, including co-opting opportunistic artists. We don’t want to let that happen again.”

Rabi Sarma’s continued resistance carries special weight — as one of the most prominent voices in Assam’s cultural space, his refusal to compromise signals that while the streets may be quiet, the sentiment against C(A)A is far from dead.

Government’s Stand on C(A)A 2019

The Government of India has consistently defended the C(A)A 2019 as a humanitarian measure. In a report by Reuters (March 12, 2024), the Home Ministry stated that the law would remove legal barriers to citizenship for refugees, giving them a “dignified life” after decades of suffering. The ministry added that many misconceptions had been spread about the law, that its implementation was delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and that it applies only to those who have faced religious persecution and have no other place of shelter except India.

The Reuters report further cited a spokesperson for the Prime Minister’s Office, who emphasised that implementing the C(A)A was a key commitment in the Bharatiya Janata Party’s 2019 election manifesto and would ‘pave the way for the persecuted to find citizenship in India.’

According to PIB (Press Information Bureau, Government of India), Home Minister Amit Shah stated in Parliament that there was “no political agenda” behind the Bill, asserting that the government’s focus was solely on ending the suffering of persecuted refugees from the three neighboring countries. The government had first brought the Bill in 2015, but could not get it passed.

The Home Minister reiterated that the Act does not affect the citizenship of Indian Muslims and argued that the law is necessary to protect minorities who are killed, forcibly converted, or compelled to flee to India from Muslim-majority nations. He explained that Muslims were excluded because they do not face religious persecution in these countries.

Here, however, arises the prime question: Why have the BJP-led Central Government and the Assam Government decided that this country of nearly 1.5 billion people should become the ideal host for some other nations’ suffering minorities? And why should Assam, with its own fragile socio-cultural balance and the Assam Accord, be turned into a dumping ground for illegal Bangladeshi immigrants?

Conclusion: A Voice That Refuses to Die

Ajit Bhuyan, Rajya Sabha MP and a prominent voice against C(A)A, shared his views with this writer in response to several questions. Key excerpts are below:

- On the Assam Accord and C(A)A:

“The Central Government and the Chief Minister of Assam have destroyed the meaning and spirit of the Assam Accord. In 1985, the then State Home Minister admitted that Assam could not take the burden of immigrants due to its socio-economic vulnerabilities. There should never have been a distinction between Hindu and Muslim Bangladeshi immigrants — but the present Governments have brought division among citizens by enacting C(A)A 2019 purely for their agenda of communal division and vote-bank politics.”

- On Clause 6:

“Where has the SIT report on Clause 6 of the Accord gone? The Chief Minister should hand over the Assam Accord to the Prime Minister for full implementation — especially Clause 6, which safeguards Assamese identity, culture, and language. Why do the Centre and State treat Assam like a laboratory, or a dumping ground, or a dustbin where all immigrants can be thrown?”

- On the Silence This Time:

“This ‘silence’ is not surrender. People are burning inside with agony, but are unwilling to trust organisations like AASU, which took leadership away from the students in 2019 and are not posing a challenge to the Government over the latest change in the C(A)A cut-off date. I don’t believe the students have failed to understand this move, but the breach of trust, lack of strategy, and poor leadership have led to this apparent inactivity.”

- On NRC:

“How can the Government play with a legal document like the NRC? When the ruling party saw a huge number of Hindu people excluded from the list, they turned it into a political game. Otherwise, they should have implemented NRC properly.”

- On Constitutional Values:

“The Governments have hurt the Constitution by striking at the idea of secularism, curbing freedom of speech, and even jailing writers and artists for their expression. India is going through an undeclared Emergency. Democracy will survive only if the Constitution is protected — but the Centre and State’s actions show only their fear.”

India’s political climate has often been unkind to dissent. Questioning government decisions can invite labels like ‘anti-national’ or ‘traitors’. In Assam, the cost of resistance has been heavy: during the 1980s agitation, students lost nearly two academic years, and in 2019, exams were cancelled again amidst curfews and protests. Five young lives were lost.

Even today, critics argue that public discourse is diverted toward communal divisions, while rural populations sink into illusions of ‘Development’ through ‘free’ schemes. Dependency grows, while corruption, deforestation, inter-state border conflicts, youth unemployment, and scams remain under-addressed. Despite this history, many right-leaning voices — including sections of the media — continue to support the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019, deepening the sense of breach of trust among protesters.

For many, the fight for Assam’s identity is not only about borders or immigration but about dignity, justice, and cultural survival — a demand that promises once made to the people be kept.

This article is not a protest. It is documentation.

A refusal to forget.

The Broken Promise lives on.